Gaze

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Gaze | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Mardi Kidwell (University of New Hampshire, USA) |

| To cite: | Kidwell, Mardi. (2023). Gaze. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: [] |

The term ‘gaze’ refers to the action of directing one’s eyes to a point in the environment (e.g., a person, object, or event). This action enables the gazer to acquire visual information, but it is also a useful social cue that is integral to the initiation, regulation and maintenance of interaction, as well as to social coordination more broadly.

Gaze plays an integral role in coordinating entry into and out of social interaction. One person’s gaze directed to another is a means of initiating interaction between two or more parties who have not previously been interacting, particularly when this is combined with an embodied approach toward the other (Mondada, 2009; Pillet-Shore, 2011). Goffman (1963) describes how situations among unacquainted individuals in public can be transformed from situations of “unfocused interaction” to “focused interaction”, that is, “ratified mutual engagement”, with a move from a brief exchange of glances (i.e., the practice of “civil inattention” usually accorded to strangers) to more sustained looking. Kendon and Ferber (1973), too, note the role of gaze in the coordinated entry of participants into ratified mutual engagement. In their classic analysis of greetings, they report on how arriving guests at a social gathering of invited, mostly acquainted individuals alternate gaze to, from, and back to the host as they approach for a greeting (which includes a “distance salutation” at the outset and a “close salutation” as the guest nears the host). Just as gazing toward another is associated with the desire, preparedness, or willingness to interact, the withdrawal of gaze is conversely associated with participants’ withdrawal from a sequence or activity within interaction (Goodwin & Goodwin, 1987; Rossano, 2012). The refusal to gaze—that is, when someone is being directed to gaze through verbal (e.g., “look at me!”) or embodied means (e.g., with a 'face hold') but still does not gaze—is associated with a refusal to be a party to interaction (Kidwell, 2006).

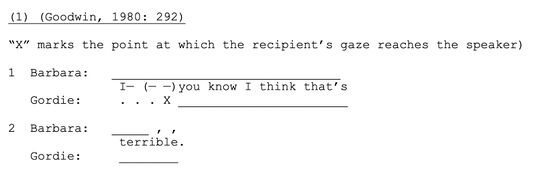

Gaze is also associated with speaker-recipient roles in interaction. Speakers gaze at recipients to show they are directing their talk to them, and recipients gaze at speakers to show that they are “doing listening” (in addition to producing, e.g., head nods, continuers, and acknowledgement tokens). Goodwin (1980, 1981) demonstrated that there is a normative orientation by speakers of English to recipient gaze. When speakers find that they do not have the gaze of a recipient, they may produce disfluencies (e.g., phrasal breaks, re-starts, pauses) to call for the recipient’s gaze. This is seen in Extract (1) below, as Barbara’s cut-off and restarts occasion Gordie’s redirection of gaze, at which point Barbara proceeds with her turn.

This orientation by the speaker to recipient gaze is not uniform, however. For example, Rossano (2012) using Italian data has demonstrated that while this pattern may hold during the speaker’s production of a multi-unit extended turn (e.g., storytelling), it does not seem to hold in the case of a speaker’s production of certain initiating actions such as questions, offers, or requests. Kidwell, on the other hand, reports on the basis of English data that speakers of another sort of initiating action, a directive, may overtly pursue the gaze of a recipient who is non-compliant, treating their gaze return as a necessary component of getting compliance, as with young children in interaction with adult caregivers (2006) and citizens in interaction with police (2013). Further, Kendrick and Holler (2017) have demonstrated that in Dutch conversation recipients’ gaze direction is associated with their preferred and dispreferred responses. Specifically, recipients tend to gaze toward speakers when producing preferred responses, and gaze away when producing dispreferred responses. In another study, Rossano et al. (2009) found that culture also affects recipient gaze patterns, with recipients in some cultures (e.g., the Tzeltal of Mexico) gazing very little at the speaker. In short, these studies demonstrate that action/activity-type, preference organization, and culture are associated with the normative patterns of recipient gaze and speakers’ efforts to procure recipient gaze in interaction.

With respect to speakers gaze towards their recipients, research shows that speakers may gaze at recipients as a means of next speaker selection (Auer, 2021; Lerner, 2003). Research also shows that speaker gaze can increase the pressure to respond in ‘non-canonical’ initiating actions such as assessments (Stivers & Rossano, 2010), and that it is associated with initiating actions such as questions (Rossano, 2012), including across a diversity of languages (Stivers, et al. 2009). Speaker gaze is also implicated in sequence expansion (gaze toward a recipient) and sequence closure (gaze withdrawal from a recipient; Rossano, 2012).

In the area of multimodal research, gaze is regularly considered in conjunction with other embodied behaviors (e.g., body orientation, facial expression, and gesture, as well as language) as part of the ‘multimodal Gestalt’ by which participants, for example, coordinate joint courses of action (Strid & Cekaite, 2021), close activity sequences (Helmer et al., 2021), and collaborate in turn construction (Hayashi, 2005). However, gaze can also be analyzed as a form of social action in its own right. Depending on how a gaze is produced (its duration, fixing on a target or not, the movement of the eye in the socket, etc.) and its placement in a sequence, it can have different consequences in an interaction. For instance, adults can arrange the features of their gaze to give young children ‘the look’ to get them to cease a course of (mis-) conduct (Kidwell, 2005), or to produce an ‘eyeroll’ as a stance display (Clift, 2021). In public and private settings, people recognize the different features of others’ gazing actions that make them instances of, for example, watching, noticing, and/or searching, and they use others’ gazes to monitor their environments for attention- and action-worthy events (Kidwell, 2009; Kidwell & Reynolds, 2022). Joining in others’ gazing actions, particularly sustained acts of watching with unacquainted others, however, is constrained by group belonging and rights of membership (Kidwell & Reynolds, 2022).

Several methods for the transcription of gaze have emerged in CA studies. These are typically given within Jefferson-style transcripts and usually also include naturalistic drawings and/or video images. In Goodwin’s classic work on gaze in conversational interaction (1981), his conventions used periods and commas to mark gaze movement toward and away from a target, respectively; an “X” to mark the arrival of gaze at a target; and a line to indicate sustained gaze toward a target. Looking again at the Goodwin excerpt presented above, Barbara is gazing at Gordon, who shifts his gaze to Barbara in line 1, then holds his gaze toward her through line 2. Barbara withdraws her gaze from Gordon at the end of line 2 as she nears the end to her turn construction unit.

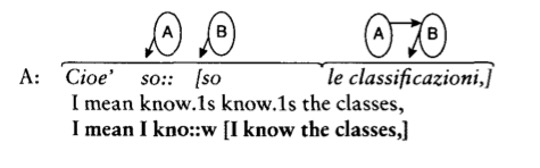

In another method for annotating gaze, Rossano (2012; see also Rossano et al., 2009) introduced a system comprised of symbols that indicate gaze direction through the use of arrows, allowing for a high degree of precision in representing where interactants are looking. Figure 1 shows a turn in Italian by Speaker A to Speaker B. Near the beginning of this turn, A is looking away and B is looking down, and then when the turn arrives at “le classificazioni” / 'the classes', A is looking at B and B is still looking down. (Rossano also uses arrows to indicate, for example, middle distance gazes, gazing at objects, gaze shifts toward an interactant, and so on)

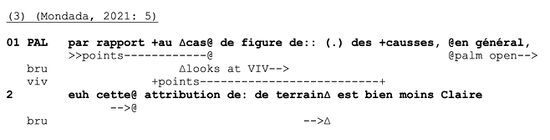

Gaze behavior as well as other bodily conduct may be transcribed in the conventions developed by Mondada (2018). In the following excerpt, speech by ‘PAL’ appears in boldface on numbered lines, and bodily conduct is temporally aligned with this speech in text below each numbered line. PAL is addressing a turn to recipients ‘bru’ and ‘viv’. Looking at line 1 and what is transcribed underneath, we can locate bru’s gaze shift to viv (denoted by the symbol Δ) by reference to PAL’s talk, as well as by reference to the pointing actions of both PAL and viv. As can be seen, in addition to a speaker’s line of talk, each participant gets a line in which their embodied actions are briefly described; each participant also gets their own unique symbol (bru Δ, PAL @, and viv +) to mark the limits of their embodied actions relative to the talk and the embodied actions of the other participants.

Finally, in a simpler approach, researchers may use a combination of video frame grabs and/or other drawings, in accompaniment with narrative descriptions of participants’ gazing behavior, and transcriptions of speakers’ talk (see e.g., Heath et al., 2010; Hepburn & Bolden, 2013).

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Additional References: