Multisensoriality

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Multisensoriality | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Lorenza Mondada (University of Basel, Switzerland) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7543-9769) |

| To cite: | Mondada, Lorenza. (2024). Multisensoriality. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/UKFMS |

Multisensoriality refers to an embodied engagement with others and/or the material world mobilizing different senses, possibly combining seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, tasting and other forms of sensoriality in and for social interaction.

An EMCA approach to sensoriality goes beyond the reduction of the senses to individual and private sensorial experiences or neuro-physiological processes. It considers instead how collectivities of participants make their sensorial experiences publicly intelligible and relevant for their ongoing activities. Moreover, the ‘sociocultural’ dimension of sensoriality is here specifically conceptualized as and through the interactional achievement of the intersubjectivity of sensing practices and activities. Thus, the focus on social interaction enables a specific approach of sensoriality:

- a praxeological approach, focusing on sensing as a practice and sometimes as an action or even an activity, rather than on the senses per se,

- a collective and intersubjective approach, referring to sensing practices as achieved in publicly accountable, witnessable ways by others and shareable with them,

- a multimodal approach, considering how sensing practices are formatted in recognizable ways, relying on language and the body to build their public and intersubjective accountability,

- a sequential approach, dealing with participants’ sensorial engagements as produced, monitored, coordinated and responded to in a way that is embedded in the sequentiality of social interaction.

According to Mondada (2021a, p. 483), multisensoriality features in social interaction in two ways: sensing for social interaction and sensing in social interaction. The first considers how the organization of social interaction relies on the participants sensing each other in and for the establishment of mutual orientations, joint actions, and intersubjectivity. The second refers to the way sensing materiality in the world is organized within social interaction as a collective engagement toward things, artifacts, tools, and other objects. The first produces a sensorial conception of social interaction, the second an interactional conception of sensing materiality in the world.

All the senses may be involved in sensing for and in social interaction. For instance, sight is involved in the management of social interaction, through gazing at each other, engaging in mutual gaze, coordinating turns-at-talk and sequences by means of looking, glancing, staring at (each) other(s) (M. H. Goodwin, 1980; C. Goodwin, 1981; Heath, 1986; Kendon, 1967; Robinson, 1998; Rossano, 2012a, 2012b). But sight is also involved in visual activities of looking at, scrutinizing, watching, and glaring at diverse aspects of the world (Goodwin, 1994, 2000a, 2000b, Heath & vom Lehn 2004, Koschmann & Zemel 2014; Lindwall & Lymer 2014; Mondada 2014, vom Lehn 2010).

Likewise, touch is involved both in managing social interaction and in exploring objects of the world within social interaction. Touch is a fundamental aspect of human sociality (Cekaite & Mondada, 2020) for various reasons. It establishes, reproduces and manifest the type of relationship of the participants, as through hugs, kisses, hand shakes, and other forms of what M. H. Goodwin (2017) calls “haptic sociality” (Kendon, 1975; Mondada et al., 2020a, 2020b). Touch also performs a diversity of actions—such as controlling, shepherding, comforting (Cekaite, 2010, 2015, 2016; Goodwin & Cekaite, 2018), also in professional practices in institutional settings (Merlino, 2020; Nishizaka, 2007, 2011; Nishizaka & Sunaga, 2015; see Routarinne, Tanio & Burdelski, 2020), including sports and other intercorporeal encounters (Meyer, 2021; Meyer & von Wedelstaedt, 2017). Moving the hands over an object also serves as a way to feel properties like shape, texture, smoothness, or rugosity. It establishes a relation between a specific haptic practice and a specific sensory feature, which can be seen by others watching the embodied movement of the hand (Mondada, 2021a; Streeck, 2009: 71). This grounds an intersubjectivity of tangible actions, including professional ones (C. Goodwin 2017; Goodwin & Smith, 2020; Mondada, 2020a; Mondémé & Kreplak 2014).

Other senses, like smell or tasting, have been mostly explored in relation to materialities rather than to interpersonal relations (although they feature also in the management and coordination of some interactions). Tasting has been studied in relation to food activities, considering how they are actually ingested and bodily appreciated (Fele, 2016, 2019; Liberman, 2013, 2018; Mondada, 2018, 2019, 2020b, 2021a, 2021b).

While vision and touch are the two aspects mainly explored in EMCA concerning the sensoriality of social interaction, hearing is an aspect mostly tacitly taken for granted as soon as participants speak, although it has been extensively studied in relation to repairs targeting difficulties of hearing (Jefferson, 2018; Schegloff, 1996; Svensson, 2020).

Studies of seeing, hearing, and speaking impairments have also demonstrated how they reveal, ex negativo, the ordinary sensorial conditions for social interaction (see for visually impaired persons Avital & Streeck, 2011; Due, 2023, Iwasaki et al., 2019; vom Lehn, 2010; Relieu, 1994, 1997; for audibly impaired participants, Egbert & Deppermann, 2012).

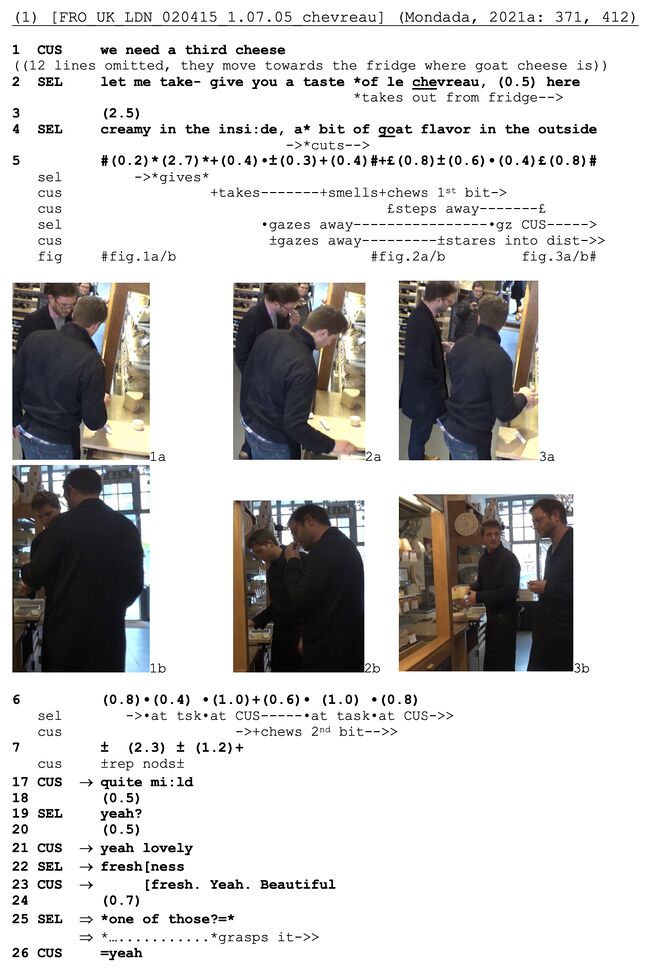

The following fragment illustrates some issues of multisensoriality (see Mondada, 2019 for another example). It documents a moment of occasioned tasting in a cheese shop in London. The transaction is recorded by two cameras, one on the front of the customer (a) and the other in front of the seller (b):

The seller proposes “a Chevreau” to the customer and gives a brief description, before handing over the sample to taste (line 4, Figure 1). The customer takes the sample and both participants immediately look away from each other (Figure 2). The customer brings the piece closer to his mouth, smells it, before tasting it (Figure 2a), while he steps away, increasing the distance between himself and the seller (Figure 3) and gazes into space (Figure 3b). The seller regularly checks what the customer is doing (line 5ff), alternating his gaze between the counter and the customer. The customer puts the remaining piece into his mouth and continues to chew.

This way of tasting presents some peculiarities. First, tasting follows the description of the sample by the seller, which is checked by the customer while also instructing his sensing experience. Second, the ongoing action involves looking at the piece, ingesting and tasting it; smelling it, before putting it into the mouth, and touching while holding a remaining bit between the fingers. This demonstrates the multisensoriality of tasting practices. Third, the tasting practice can treat the given sample as a unique piece put into the mouth, or can involve segmenting the piece of cheese into two bites. This splitting has several organizational consequences. It affects the sequential organization of tasting, by giving the occasion to prolong and delay the completion of the tasting experience. It also affects the sensorial organization of the tasting; by preparing a second bite to taste, the sensory experience is expanded, a first impression can be checked on the basis of a second, other sensorial qualities are made available beside the most immediate ones. Beside taste, other senses are mobilized: the customer holds the remaining piece in his hand, engaging in some haptic feeling with the fingers. In this way, the customer orchestrates a silent multisensorial tasting experience. Fourth, tasting, smelling and touching the sample are achieved within a particular participation framework: when the seller proposes and describes the cheese the attention of both participants alternates between themselves and the sample; but when the customer engages in tasting, he withdraws from a reciprocal gaze or common look at the sample and exclusively focuses on the tasting, looking in the void. So, mutual embodied orientations are suspended during tasting, with eventually the seller unilaterally intermittently monitoring the customer. This particular participation framework is dissolved at completion of the tasting (see Mondada, 2018 for a systematic description of this format).

The tasting proper (line 7) lasts for some time, before the customer produces repeated nods and a positive assessment (line 8). This is followed by the seller asking for confirmation (line 10) and the customer confirming with an upgrade (line 12). The seller adds another assessment (line 13), and the customer aligns with it again, and produces a new upgrade (line 14). At this point, the seller asks a yes/no question, projecting a confirmation of the quantity to buy (line 16), while grasping the piece of cheese about to be bought, anticipating on the sale— quickly confirmed by the customer (line 17).

This fragment shows several features specific of multisensorial practices:

- Various senses are generally mobilized within an activity, in a way that builds a holistic sensorial experience, but also in ways that order and hierarchize them (like in tasting sessions where they are successively and analytically mobilized). The use of different senses also depends on the local praxeological ecology, that is the relevant environment for the ongoing action (e.g. eating with a fork does not enable the person to feel the texture of the food with their hands).

- These sensorial engagements are embedded in the ongoing activity and are relevant to it, contributing to its progressivity.

- They are seen, heard and witnessed by others in that way, who, on this basis, also engage in contributing to the activity, either by sensing together and sensuously interacting together or by producing a next relevant action made possible and relevant by the person sensing. This defines the intersubjectivity and interactivity of multisensorial practices.

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Avital, S. & Streeck, J. (2011). Terra incognita: Social interaction among blind children. In J. Streeck, C. Goodwin, & C. LeBaron (eds.), Embodied interaction: Language and body in the material world (pp. 169-181). Cambridge University Press.

Cekaite, A. (2010). Shepherding the child: Embodied directive sequences in parent-child interactions. Text & Talk, 30(1), 1-25.

Cekaite, A. (2015). The coordination of talk and touch in adults’ directives to children: Touch and social control. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 48(2), 152-175. Cekaite, A. (2016). Touch as social control: Haptic organization of attention in adult–child interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 92, 30-42.

Cekaite, A. & Mondada, L. (eds.) (2020). Touch in social interaction: Touch, language, and body. Routledge.

Due, B. (ed.). (2023). The practical accomplishment of blind people’s ordinary activities. Routledge.

Egbert, M., & Deppermann, A. (eds.) (2012). Hearing aids communication. Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.

Fele, G. (2016). Il paradosso del gusto. Società Mutamento Politica, 7(14), 151-74.

Fele, G. (2019). Olfactory objects: Recognizing, describing and assessing smells during professional tasting sessions. In D. Day & J. Wagner (eds.), Objects, bodies and work practice (pp. 250-284). Multilingual Matters.

Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. Academic Press.

Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606-633.

Goodwin, C. (2000a). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489-1522.

Goodwin, C. (2000b). Practices of color classification. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 7(1-2), 19-36.

Goodwin, C. (2017). Co-operative action. Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, C., & Smith, M.C. (2020). Calibrating professional perception through touch in geological fieldwork. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (eds.), Touch in social interaction: Touch, language, and body (pp. 269-287). Routledge.

Goodwin, M. H. (1980). Processes of mutual monitoring implicated in the production of description sequences. Sociological Inquiry, 50(3‐4), 303-317.

Goodwin, M. H. (2017). Haptic sociality: The embodied interactive constitution of intimacy through touch. In C. Meyer, J. Streeck, & J.S. Jordan (eds.), Intercorporeality: Emerging socialities in interaction (pp. 73-102). Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, M. H. & Cekaite, A. (2018). Embodied family choreography. Practices of control, care and mundane creativity. Routledge.

Heath, C. (1986). Body movement and speech in medical interaction. Cambridge University Press.

Heath, C., & Luff, P. (2000). Technology in action. Cambridge University Press .

Heath, C., & vom Lehn, D. (2004). Configuring reception: (Dis-)Regarding the ‘spectator’ in museums and galleries. Theory, Culture & Society, 21(6), 43-65.

Iwasaki, S., Bartlett, M., Manns, H. & Willoughby, L. (2019). The challenges of multimodality and multi-sensoriality: methodological issues in analyzing tactile signed interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 143, 215-227.

Jefferson, G. (2018). Repairing the broken surface of talk: Managing problems in speaking, hearing, and understanding in conversation. Oxford University Press.

Kendon, A. (1967). Some functions of gaze-direction in social interaction. Acta Psychologica, 26, 22-63.

Kendon, A. (1975). Some functions of the face in a kissing round. Semiotica, 15(4), 299-334.

Koschmann, T., & Zemel, A. (2014). Instructed objects. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann and M. Rauniomaa (eds.), Interacting with objects: Language, materiality, and social activity (pp. 357-378). John Benjamins.

Liberman K. (2013). More studies in ethnomethodology. SUNY.

Liberman, K. (2018). Objectivation practices. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 1(2).

Lindwall, O., & Lymer, G. (2014). Inquiries of the body: Novice questions and the instructable observability of endodontic scenes. Discourse Studies, 16(2), 271-294.

Merlino, S. (2020). Professional touch in speech and language therapy for the treatment of post-stroke aphasia. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (eds.) Touch in social interaction: Touching moments (pp. 197-223). Routledge.

Meyer, C. (2021). Co-sensoriality, con-sensoriality, and common-sensoriality: the complexities of sensorialities in interaction. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 4(3).

Meyer, C., & von Wedelstaedt, U. (eds.) (2017). Moving bodies in interaction-Interacting bodies in motion: Intercorporeality, interkinesthesia and enaction in sports. John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2014). Requesting immediate action in the surgical operating room: time, embodied resources and praxeological embeddedness. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & P. Drew, P. (eds.) Requesting in social interaction (pp. 271-304). John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2018). The multimodal interactional organization of tasting: Practices of tasting cheese in gourmet shops. Discourse Studies, 20(6), 743-769.

Mondada, L. (2019). Rethinking bodies and objects in social interaction: a multimodal and multisensorial approach to tasting. In U. Kissmann & J. van Loon (eds.) Discussing new materialism (pp. 109-134). Springer.

Mondada, L. (2020a). Sensorial explorations of food: How professionals and amateurs touch cheese in gourmet shops. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (eds.) Touch in social interaction: Touch, language, and body (pp. 288-310). Routledge.

Mondada, L. (2020b). Audible sniffs: Smelling-in-interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53(1), 140-163.

Mondada, L. (2021a). Sensing in social interaction: The taste for cheese in gourmet shops. Cambridge University Press.

Mondada, L. (2021b). Language and the sensing body: How sensoriality permeates syntax in interaction. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 664430.

Mondada, L., Bänninger, J., Bouaouina, S.A., Camus, L., Gauthier, G., Koda, M., Svensson, H., Tekin, B.S. & Hänggi, P. (2020a). Human sociality in the times of the Covid‐19 pandemic: A systematic examination of change in greetings. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 24(4), 441-468.

Mondada, L., Monteiro, D. & Tekin, B.S. (2020b). The tactility and visibility of kissing: intercorporeal configurations of kissing bodies in family photography sessions. In A. Cekaite and L. Mondada (eds.) Touch in social interaction: Touch, language, and body (pp. 54-80). Routledge.

Mondémé, C., & Kreplak, Y. (2014). Artworks as touchable objects. Guiding perception in a museum tour for blind people. In M. Nevile, P. Haddington, T. Heinemann, and M. Rauniomaa (eds.), Interacting with objects (pp. 289-311). John Benjamins.

Nishizaka, A. (2007). Hand touching hand: referential practice at a Japanese midwife house. Human Studies, 30(3), 199-217.

Nishizaka, A. (2011). Touch without vision: referential practice in a non-technological environment. Journal of Pragmatics, 43, 504-520.

Nishizaka, A. (2020). Multi-sensory perception during palpation in Japanese Midwifery practice. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(1).

Nishizaka, A. & Sunaga, M. (2015). Conversing while massaging: Multidimensional asymmetries of multiple activities in interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 48(2), 200-229.

Relieu, M. (1994). Les catégories dans l’action: l’apprentissage des traversées de rue par des non-voyants. In B. Fradin, L. Quéré, & J. Widmer (eds.) L'enquête sur les catégories: de Durkheim à Sacks (pp. 185-218). EHESS.

Relieu, M. (1997). L’observabilité des situations publiques problématiques: genèse des propositions d’aide a des non-voyants. In A. Marcarino (ed.) Analisi della conversazione e prospettive di ricerca in etnometodologia. Atti del Convegno internazionale (Urbino, 11-13 luglio 1994) (pp. 219-234). QuattroVenti.

Robinson, J.D. (1998). Getting down to business: talk, gaze, and body orientation during openings of doctor-patient consultations. Human Communication Research, 25(1), 97-123.

Rossano, F. (2012a). Gaze behaviour in face-to-face interaction. Ph.D. dissertation. Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics Series.

Rossano, F. (2012b). Gaze in conversation. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (eds.) The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 308-329). Wiley-Blackwell.

Routarinne, S., Tanio, L.E. & Burdelski, M. (eds.) (2020). Special issue: Human-to-human touch in institutional settings. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 3(1).

Schegloff, E.A. (1996). Some practices for referring to persons in talk-in-interaction: a partial sketch of a systematics. In B.A. Fox (ed.) Studies in Anaphora (pp. 437-485). John Benjamins.

Streeck, J. (2009). Gesturecraft: The manufacture of meaning. John Benjamins.

Svensson, H. (2020). Establishing shared knowledge in political meetings: Repairing and correcting in public. Routledge.

Vom Lehn, D. (2010). Discovering “experience-ables”: socially including visually impaired people in art museums. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(7-8), 749-769.

Wiggins, S. (2004). Talking about taste: using a discursive psychological approach to examine challenges to food evaluations. Appetite, 43(1), 29-38,

Additional References:

Howes, D. (2005). Empire of the Senses. Berg.