Multimodal Gestalt

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Multimodal Gestalt | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Lorenza Mondada (University of Basel, Switzerland) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7543-9769) |

| To cite: | Mondada, Lorenza. (2024). Multimodal Gestalt. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/Q7HP8 |

The notion of “multimodal Gestalt” refers to a recurrent accountable arrangement of various multimodal resources that are mobilized by the participants and constitute a methodic practice or action. These resources are perceived and treated as such by the participants, who can orient both analytically to their single details and holistically to the whole that they constitute (De Stefani, 2022; Mondada, 2014a: 139-140, 2014b: 98, 2016: 344). An example of multimodal Gestalt is a request accomplished by the requester pointing to the requested object while also gazing at it, leaning, and stepping towards it: the pointing gesture is performed within this wider constellation of embodied movements, which are perceived as making sense together in that context (by contrast to other movements, not associated with the Gestalt).

In a multimodal Gestalt, resources are seen and heard as mobilized together although they are generally initiated at different moments in time, have different durations, and specific trajectories. For example, though one can step towards an object and then point at it, while staring at it continuously, these mobile, gestural, and visual practices are part of the same Gestalt. Thus, a multimodal Gestalt constitutes a dynamic complex temporal format that emerges, transforms, and is closed in time, characterized by multi-layered resources (Mondada, 2018). Moreover, the Gestalt is sequentially positioned and organized, as the action it accomplishes unfolds and is responded to. Finally, the way resources constituting a Gestalt are assembled crucially depends on the material ecology in which they emerge.

Methodologically, the notion of multimodal Gestalt enables the analyst to treat assemblages of multiple resources (instead of singling out one embodied resource treated in relation to another, typically talk), and to consider the sequential environment in which the Gestalt emerges and in which it situatedly acquires its relevance and intelligibility. Gestalts might be considered in their indexicality, or might be seen as stabilized and grammaticalized (Stukenbrock, 2021).

More generally, the notion of Gestalt has been previously used in EMCA in at least two ways, referring to linguistic Gestalts and to Gestalt contextures—which the notion of multimodal Gestalt might include. On the one hand, in interactional linguistics, Auer (1996, 2009) and Selting (2005) use the term to refer to the dynamic emergent formats characterizing the unfolding of turns-in-progress, combining prosodic, syntactic, and pragmatic features. In particular, Auer (1996) prefers to speak of “Gestalt” rather than of “structure”, highlighting its temporal character and its projecting potentials, including the real-time perception of its emergent form (p. 59). This is further elaborated in Auer’s notion of online syntax. Syntax emerges in time, through the way a possible trajectory of a syntactic Gestalt is projected (opened), generates expectations, and is finally completed (closed) (Auer, 2009: 4).

On the other hand, in ethnomethodology, the concept of Gestalt has inspired Garfinkel, referring to Gurwitsch’s “gestalt contexture” (1957, see Eisenmann & Lynch, 2021; Lynch & Eisenmann, 2022; Meyer, 2022). Revisiting the notion of Gestalt in a phenomenological way, Gurwitch speaks of “gestalt contexture” to refer to the coherence of the interrelated components of the whole. Their coherence is established within the perceptual field of the observer. Garfinkel moves from the perceived phenomenal qualities to a focus on the practices producing these qualities. His praxeological focus is not on the figure/ground relation observable between visual objects, but on the action that achieves the visibility of these objects and their relations, moment-by-moment and here-and-now within social interaction (Garfinkel, 2021; Lynch & Eisenmann, 2022; Meyer, 2022). Queuing constitutes a prototypical example (Garfinkel & Livingston, 2003): the organization of the queue is not reducible to a line, as visible on photographs; rather, it is a spatial and temporal achievement of bodies progressively assembling in a certain way, resulting from the actions of finding the end-of-the-queue, witnessably joining the queue, holding and continuing the structure of the queue, etc.

The uses of Gestalt for the analysis of multimodality somehow refer to this double tradition. Heath (1986: 97), mentioning Gurwitsch and Garfinkel’s documentary method of interpretation, uses the notion of Gestalt to refer to the multimodal organization of action, pinpointing the reflexive relation between action and movements, between perceived action and underlying presupposed patterns. Mondada (2014a, 2014b) speaks of multimodal Gestalt in relation to the accountability of action achieved by multiple linguistic and embodied resources, referring to its multi-layered order, its embeddedness in the sequential organization, the flexibility of its temporal arrangement, and the orientation of the participants making relevant these multiple details as belonging to the same assemblage, against the background of other actions.

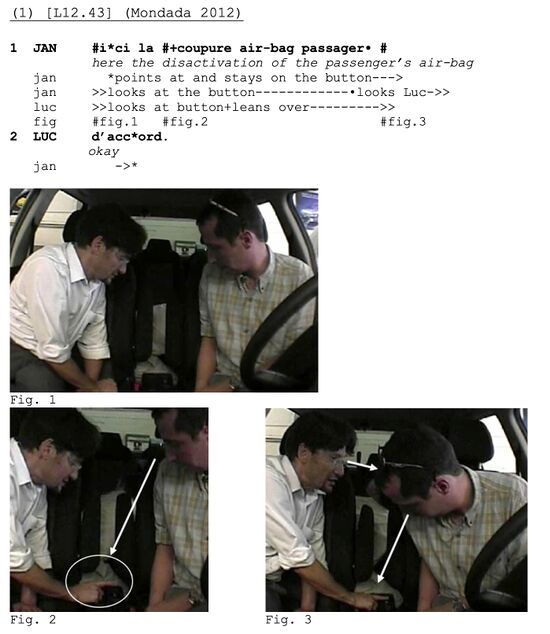

In order to give two contrastive examples of multimodal Gestalts, let’s compare the following two extracts: in a garage showroom, a car seller (Jan) successively explains to two customers (Luc and Guy) some functionalities of the car they just bought. We join the first instance in which Jan explains to Luc where the button deactivating the air-bag security is:

While uttering the deictic expression “ici”/‘here’, Jan points at the feature he is describing, a button disactivating the air-bag. His own gaze is on the button, as well as, since the beginning of the turn, his recipient’s gaze (Figure 1). Luc not only gazes but also bends over, looking carefully, as Jan utters the noun phrase describing the feature (line 1, Figure 2). At turn completion, Jan gazes at Luc (Figure 3), who immediately positively responds (line 2), displaying his understanding and closing the sequence.

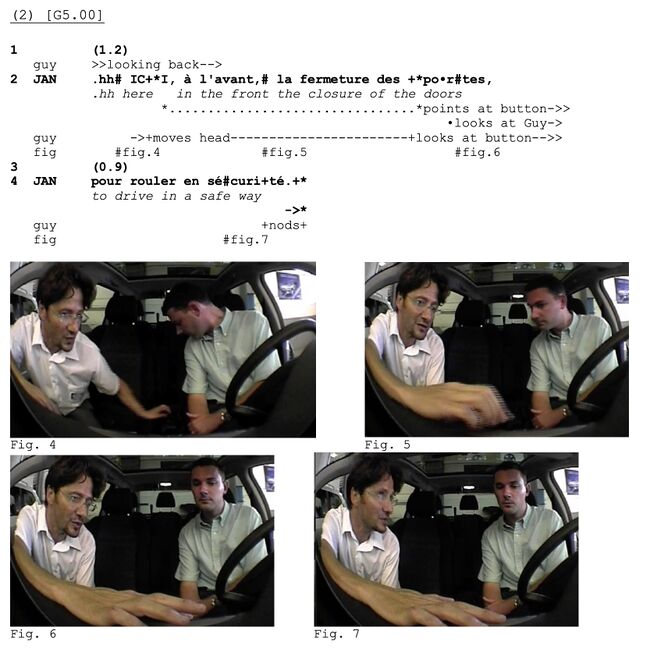

In the next extract, Jan explains to Guy the button activating the closure of the doors.

Like in the previous instance, Jan begins his turn with “ici”/‘here’. However, contrary to the previous case, at that point his recipient, Guy, is still looking at something else (Figure 4). Guy begins to move his head at the beginning of Jan’s turn, while Jan adds a spatial description (“à l’avant”/‘on the front’ line 2), orienting to the fact that Guy is still turned to the back. Only then Jan produces a noun phrase describing the feature, while continuously extending his hand, which reaches the object described on its final word (Figures 5-6). At this point too, Jan gazes at Guy, who is now looking at the referred to feature. After a silence, Jan, visibly orienting to Guy’s absence of response, increments his turn with an infinitive phrase (line 4), still having his pointing fingers on the button and looking at Guy (Figure 7)—thereby offering a new opportunity to respond. Guy finally acknowledges the explanation with a small nod and the sequence is closed.

Despite the fact that in both cases a similar verbal format is used (with the proximal deictic and a noun phrase), and the speaker points at the object referred to, the two occurrences show important differences, accounting for two distinct multimodal Gestalts (see Mondada, 2012 for a systematization). The first Gestalt, in which the deictic expression co-occurs with a pointing gesture, is adopted for introducing an object that is in the line of sight of the recipient and therefore does not necessitate a reorientation of their attention. This Gestalt works as a device introducing a new referent singled out within the material environment. Alternatively, when the speaker introduces a referent located elsewhere than where the recipient is currently looking at, a similar verbal construction is used, but within a different distribution of gesture and gaze. In this second Gestalt, the pointing gesture occurs later, mostly at the end of the description, concurring with the noun phrase verbalizing the object, adjusting to the reorientation of the recipient’s gaze. In this second Gestalt “ici”/’here’ works as an attention-getting device, announcing that something has to be searched for and seen, projecting imminent pointing. Moreover, whereas in the first Gestalt the verbal construction is quite minimal (deictic + noun phrase), this second Gestalt also includes other verbal resources that expand the turn, like further specifications, or extensions of the turn, all orienting and adjusting to the late gaze movement of the recipient.

These two configurations show the importance of the temporal and interactional arrangement of a multimodal composite Gestalt and the need to describe such Gestalts in order to capture in detail their praxeological and interactional meaning (for other examples see Mondada, 2023). For the cases illustrated here, the practice of indexically referring to a new object can neither be reduced to the verbal deictic expression nor its co-occurrence with a pointing gesture, but has to take into consideration in an integrated way a) the multiple multimodal details assembled in the Gestalt and composing it, b) their temporal arrangements, c) their sequential unfolding, d) the way in which these details as well as the Gestalt as a whole are interactively treated by all the participants.

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Auer, P. (1996). On the prosody and syntax of turn-taking. In E. Couper-Kuhlen & M. Selting (eds.), Prosody and conversation (pp. 57-100). Cambridge University Press.

Auer, P. (2006). Increments and more. Anmerkungen zur augenblicklichen Diskussion über die Erweiterbarkeit von Turnkonstruktionseinheiten. In A. Deppermann, R. Fiehler, & T. Spranz-Fogasy (eds.), Grammatik und Interaktion (pp. 279-294). Verlag für Gesprächsforschung.

De Stefani, E. (2022). On gestalts and their analytical corollaries: A commentary to the special issue. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 5(1).

Eisenmann, C., & Lynch, M. (2021). Introduction to Harold Garfinkel’s ethnomethodological “misreading” of Aron Gurwitsch on the phenomenal field. Human Studies, 44(1), 1-17.

Garfinkel, H. (2021). Ethnomethodological misreading of Aron Gurwitsch on the phenomenal field. Human Studies, 44(1), 19-42.

Garfinkel, H., & Livingston, E. (2003). Phenomenal field properties of order in formatted queues and their neglected standing in the current situation of inquiry. Visual Studies, 18(1), 21-28.

Gurwitsch, A. (1957). Théorie du champ de la conscience. Desclés de Brouwer [The field of consciousness. 1964. Duquesne University Press.].

Heath, C. (1986). Body movement and speech in medical interaction. Cambridge University Press.

Lynch, M., & Eisenmann, C. (2022). Transposing Gestalt phenomena from visual fields to practical and interactional work: Garfinkel’s and Sacks’ social praxeology. Philosophia Scientiae, 26(3), 95-122.

Meyer, C. (2022). The phenomenological foundations of ethnomethodology’s conceptions of sequentiality and indexicality. Harold Garfinkel’s references to Aron Gurwitsch’s “field of consciousness”. Gesprächsforschung Online, 23, 111-144.

Mondada, L. (2012). Deixis: An integrated interactional multimodal analysis. In P. Bergmann & J. Brenning (eds.), Prosody and embodiment in interactional grammar (pp. 173-206). De Gruyter.

Mondada, L. (2014a). The local constitution of multimodal resources for social interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 65, 137-156.

Mondada, L. (2014b). Pointing, talk and the bodies: Reference and joint attention as embodied interactional achievements. In M. Seyfeddinipur & M. Gullberg (eds.), From gesture in conversation to visible utterance in action (pp. 95-124). John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(2), 336-366.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106.

Mondada, L. (2023). Requesting in shop encounters. multimodal gestalts and their interactional and institutional accountability. In D. Barth-Weingarten & M. Selting (eds.), New perspectives of interactional linguistic research. John Benjamins.

Selting, M. (2005). Syntax and prosody as methods for the construction and identification of turn-constructional units in conversation. In A. Hakulinen & M. Selting (eds.), Syntax and lexis in conversation: Studies on the use of linguistic resources in talk-in-interaction (pp. 17-44). John Benjamins.

Stukenbrock, A. (2021). Multimodal gestalts and their change over time: Is routinization also grammaticalization? Frontiers in Communication, 6, 662240.

Additional References:

Koffka, K. (1922). Perception: An introduction to the Gestalt-Theorie. The Psychological Bulletin, 19(10), 531–585.

Wertheimer, M. (1985 [1924]). Über Gestalttheorie. Gestalt Theory, 7(2), 99–120.