Candidate understanding

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Candidate understanding | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Salla Kurhila (University of Helsinki, Finland) (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0426-3660) & Daniel Radice (University of Helsinki, Finland) |

| To cite: | Kurhila, Salla, & Radice, Daniel. (2023). Candidate understanding. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/756QN |

A candidate understanding is a turn-in-talk in which the speaker presents for confirmation or disconfirmation their understanding of a previous speaker's turn. They usually, but not necessarily, relate to the immediately preceding turn (Schegloff, et al. 1977). Candidate understandings are also referred to simply as ‘candidates’, normally as part of the phrase ‘to offer a candidate’.

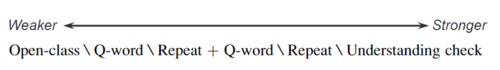

Following from the term's origins in the work of Schegloff et al. (1977) on repair organisation, candidate understandings are most often presented as part of an other-initiated repair (OIR) sequence referred to as an ‘understanding check’. In an understanding check, the recipient presents their understanding of the trouble-source turn (their candidate understanding) and seeks confirmation of that understanding from the trouble-source speaker (Hayashi & Hayano 2013). In the typology of OIR formats outlined by Schegloff, et al. (1977), understanding checks are the most specific, or ‘strongest’, format in terms of their capacity to locate the trouble source, as they not only precisely locate the trouble source but also offer a possible solution to the trouble. The weakest format in this typology is open-class questions such as “what?” and “huh?” (Drew 1997), with several other OIR formats being located in between, as summarised in the following diagram (Hayashi & Hayano 2013):

Figure 1: OIR Formats (Hayashi & Hayano 2013)

Below is a simple example of a candidate understanding:

(Schegloff, et al. 1977: 368) 01 A: Why did I turn out this way. 02 B: -> You mean homosexual? 03 A: Yes

In addition to cases like the one above, which reword part of the original message, Hayashi & Hayano (2013) identify a second form of candidate understanding which is presented as an add-on that is structurally dependent on the design on the prior speaker's turn, as in the following example:

(Hayashi & Hayano 2013: 298)

01 Kum: eh (.) donogurai sundeta no:?

RC how.long were.living FP

How long did you stay/live?

02 Mik: –> chiba ni?

Chiba in

In Chiba?

03 Kum: u[:n.

Yeah.

In agreement with the typology of Schegloff, et al. (1977), a cross-linguistic study by Dingemanse, et al. (2015) found understanding checks to be the most specific of three basic types of repair initiation common to 12 languages across 8 language families. The study refers to these as 'restricted offers', with the two less specific types being ‘open requests’, which correspond to open-class questions, and ‘restricted requests’, which cover several types within the middle of the OIR typology shown above. The authors find that restricted offers are more common in less trouble-prone contexts, such as those where there is no noise of overlap, and conclude that people thus tend to use a more specific type of repair initiation if they are able to. This specificity principle "reveals an element of altruism in how people initiate repair in conversation" (2015: 7), as understanding checks mean greater work for the repair initiator compared to a simple "huh?".

The use of candidate understandings has been examined in various contexts. In her examination of linguistically asymmetric conversations, Kurhila (2006) finds that candidate understandings are often used by the more competent speaker to resolve language-related problems. Instead of producing repair initiations that would leave it to the second language speaker to modify their prior talk, the more competent speakers produce candidate understandings, which not only serve to signal a problem but also attempt to remedy it. Candidate understandings thus function as a way to move the conversation forward, to orient to the progress of interaction rather than to the problem.

Candidate understandings have also been examined in contexts that do not clearly fit into the spectrum of OIR types presented above. For example, some candidate understandings do not feature clear signs that the speaker has had trouble understanding the previous turn, leaving it unclear whether their primary function is to check understanding. Antaki (2012) examined a group of such cases which he terms ‘disaffiliative candidate understandings’. In this distinction, affiliative candidate understandings are those like the examples given above: they address some problem of understanding, such as the place being referred to, and propose some new information to resolve the problem. They therefore promote the action that the previous speaker is pursuing. Disaffiliative candidate understandings, on the other hand, address no visible problem and recycle information that should already be clear to both participants. Antaki argues that such utterances are designed to frustrate rather than promote the other speaker’s action, and that they “bring out something that the speaker should be doing or saying” (Antaki 2012: 544). Schegloff (1996), meanwhile, examines the candidate understandings presented as part of the action of ‘confirming an allusion’. These are in one sense understanding checks, but differ from normal OIR in that they are attempts to guess a meaning that has been alluded to by the previous speaker.

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Antaki, C. (2012). Affiliative and disaffiliative candidate understandings. Discourse Studies 2012 14(5), 531–547

Dingemanse, M., Roberts, S.G., Baranova, J., Blythe, J., Drew, P., Floyd, S., Gisladottir, R. S., Kendrick, K. H., Levinson, S. C., Manrique, E., Rossi, G., & Enfield, N. J. (2015). Universal Principles in the Repair of Communication Problems. PLOS ONE 10(9): e0136100.

Drew, P. (1997). “Open”-class repair initiators in response to sequential sources of troubles in conversation. Journal of Pragmatics 28, 69–101.

Hayashi, M., & Hayano, K. (2013). Proffering insertable elements: a study of other-initiated repair in Japanese. In Hayashi, M., Raymond, G., & Sidnell, J. (Eds.). (2013). Conversational Repair and Human Understanding (pp. 293–321). Cambridge University Press.

Kurhila, S. (2006). Second Language Interaction. John Benjamins.

Schegloff, E. A. (1996). Confirming Allusions: Toward an Empirical Account of Action. American Journal of Sociology, 102(1), 161–216.

Additional References: