Announcing

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Announcing | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Danielle Pillet-Shore (University of New Hampshire, USA) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4757-4082) |

| To cite: | Pillet-Shore, Danielle. (2023). Announcing. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/BV9YQ |

The terms announcing and announcement are used to describe a declarative utterance presented by its speaker as an intended recipient-informing about something noteworthy. (‘Announcing’ is a speaker-side term, while ‘informing’ is a recipient-side term.) Announcing is a social action done by speakers displaying a knowing epistemic stance (e.g., Heritage, 2012; Schegloff, 2007; Terasaki, 2004 [1976]). It is not, however, criterial “that speakers know in fact that their intended recipients have not heard the impending news” (Terasaki, 2004 [1976]:175). A speaker’s announcement may report on:

- a unilaterally-experienced event asymmetrically within the speaker’s epistemic domain which may be temporally and/or spatially dislocated from the here-and-now conversation (e.g., Goodwin’s [1979] “I gave up smoking cigarettes::. (0.4) I-uh: one-one week ago t’da:y acshilly”; Heritage, 2012; Pillet-Shore, 2018b; Terasaki, 2004 [1976]), as in Excerpts (1), (2), and (3);

- a multilaterally-experienceable, publicly and concurrently perceivable referent that is temporally and spatially located in the here-and-now conversation (Pillet-Shore, 2021:14-16; Schegloff, 2007:74), as in Excerpts (4), (5), and (6).

Announcing can be done as a volunteered or elicited action. When volunteered, announcing is launched by a teller “to convey ‘news’ on their own initiative” (Schegloff, 2007:37). Such announcing has been identified as a first pair part (FPP) in an adjacency pair sequence (ibid:59, 74-75). There is debate about whether this type of announcing embodies conditional relevance, with one view suggesting that depends upon how it is visibly and audibly designed (Stivers & Rossano, 2010:9, 17-18). According to another view, a FPP announcement makes relevant next a second pair part (SPP) response that displays an orientation toward what has been told as in fact ‘news’ or not, and that displays a stance toward/assesses the reported event/experience (Schegloff, 2007:37; Terasaki, 2004 [1976]).

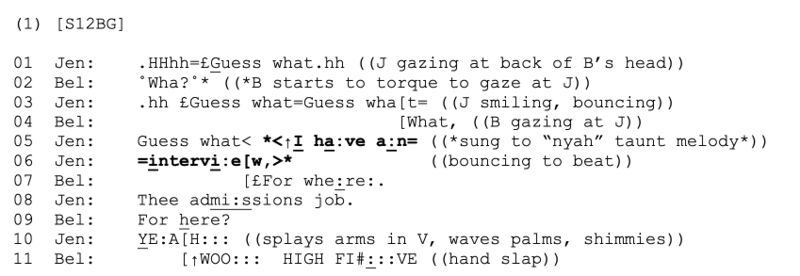

When announcements are done through an adjacency pair sequence, they regularly occur “over turn series larger than the two-turn pair” (Terasaki, 2004 [1976]:176). One place that an announcement sequence can be expanded is before its FPP, with a “pre-announcement” (Schegloff, 2007:37-42; Terasaki, 2004 [1976]), as in Excerpt (1), which shows Jen volunteering an announcement as she enters her shared apartment and encounters her roommate Bella:

*https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyah_nyah_nyah_nyah_nyah_nyah

*https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nyah_nyah_nyah_nyah_nyah_nyah

In Excerpt (1) at line 1, Jen delivers a pre-announcement FPP that is lexically designed with the “canonical,” “virtually dedicated phrase ‘guess what’” (Schegloff, 2007:38). Such pre-announcements alert the recipient “that what is to follow is built to be an informing” (Schegloff, 2007:39). Jen’s recipient Bella quietly yet immediately produces a “go-ahead” SPP response (ibid:40) at line 2 by repeating the question word that Jen used at line 1. At lines 3-5, Jen continues her pre-announcement FPP actions as a method of both establishing a participation framework with Bella (providing Bella time to turn her gaze to Jen), and multimodally displaying her stance toward her projected news: she visibly and audibly smiles as she performs a full-body bouncing motion to convey a positive, happy stance toward her upcoming announcement of good news. At lines 5-6, Jen delivers her base FPP announcement proper—a declarative utterance produced as an intended informing of Bella, reporting her unilaterally-experienced event of being offered a job interview. Jen continues her multimodal stance display by prosodically producing her announcement with a common children’s taunt melody/chant. After two insert sequences (at lines 7-10), Bella delivers her base SPP response to Jen’s announcement at line 11 by displaying an orientation toward what has been told as in fact ‘news’, and displaying an empathic, mirrored and echoed positive stance toward the reported event/experience (Pillet-Shore, 2018b; Schegloff, 2007:37; Terasaki, 2004 [1976]).

While Excerpt (1) shows how a speaker uses a pre-announcement (a sequence-organizational resource) to alert the recipient of an upcoming informing, Excerpt (2) shows how a speaker uses other (turn design) resources to alert his recipient of an emergent informing. Here, Chase is talking to his brother Mark on a Sunday evening about how Chase just spent his weekend working on their family’s rental house and learning some family gossip (cf. Dunbar, 2004). At line 3, Chase does announcing the news that their cousin Darin is engaged as a volunteered action:

Chase multimodally prepares for, and thus visibly and audibly displays his orientation to the bolded portion of his utterance (at line 3) as newsworthy by doing an eyebrow raise, slowing the pace of his talk, fully enunciating each sound, starting to smile, and bringing his gaze to meet his recipient Mark’s just as he delivers the locally initial recognitional third person reference (Schegloff, 1996) to their cousin by his first name. At line 4, Mark delivers his SPP response to Chase’s announcement, treating what has been told as in fact ‘news.’

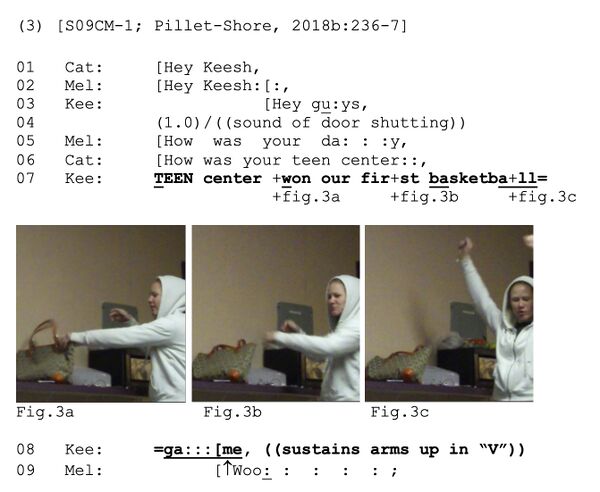

Announcing can also be done as an elicited action. One regular site for such announcements is in response to a personal state sequence inquiry (Pillet-Shore, 2018a:220-222, 2018b:235-237). Excerpt (3) shows a personal state sequence inquiry FPP at lines 5-6, in response to which recently-arrived Keesha delivers an announcement SPP at lines 7-8:

Keesha does announcing by delivering a declarative utterance presented as an intended informing of her recipients, reporting on a temporally and spatially dislocated event that she has recently unilaterally experienced. Keesha builds her single turn-constructional unit (TCU) response to include stance-marking embodiments that audibly (using marked/emphatic prosody) and visibly (e.g., shooting her arms upward) enact a positive personal state while invoking a selected previous activity/experience positioned as precipitating her positive state. Thus, rather than responding to her roommates’ personal state inquiries with a lexical value state (e.g., “Good”; Sacks, 1975), Keesha delivers an announcement that indexes a selected previous activity/experience (Pillet-Shore, 2018b), thereby proffering this as a talkable. At line 9, recipient Mel delivers an empathic response (Pillet-Shore, 2018b:237) that displays a positive stance toward Keesha’s reported event/experience.

A speaker’s volunteered announcement may also report on and call attention to a publicly and concurrently perceivable referent (Pillet-Shore, 2021:14-16; Schegloff, 2007:74), as in Excerpt (4), which shows arriving Nolan delivering an announcement at line 2 as he enters his friends’ apartment:

Nolan’s utterance at line 2 is hearable as announcing a consumable beverage offering (Pillet-Shore, 2008:29, 2018a:226) that he has brought to share with others since it is a declarative utterance delivered by a speaker displaying a knowing epistemic stance. This view is consistent with Schegloff’s (2007:74) presentation of the following excerpt, arguing that, “Announcements, noticings, or, more generally, tellings can be first pair parts in their own right, making relevant a sharing of the noticing (as in Excerpt [5])”:

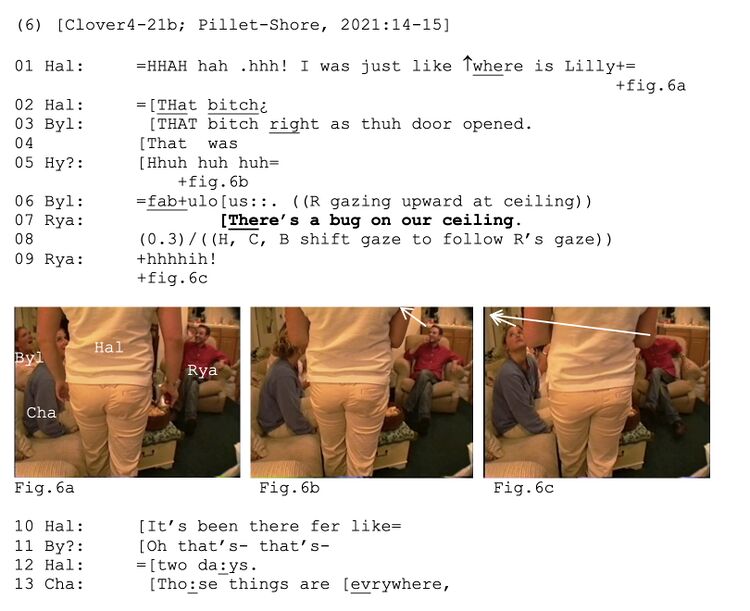

In his discussion of the above excerpt, Schegloff leaves unclear whether line 2 is doing announcing, or noticing, or both. Subsequent studies of similar actions (e.g., Goodwin & Goodwin, 2012:276-277) only use the term “noticing” to describe such utterances (containing, e.g., deictic terms) “that attempt to bring a seeable field into view, or summon someone to look at a particular phenomenon” (ibid). This literature thus renders as equivocal what makes an action recognizable (to participants, and then to analysts) as doing “noticing” versus “announcing” a here-and-now referent. Proposing a solution to this terminological analytic problem, Pillet-Shore (2021) analyzes sequence-initial actions in copresent encounters that call attention to a concurrently perceivable referent (as in Excerpts 4 and 5 above), including when people “audibly point” (Pillet-Shore, 2021:11) to a newcomer’s arrival (e.g., “↑There she is”), or deliver an utterance such as line 7 in Excerpt (6):

At line 7, Ryan reports on and calls attention to a publicly and concurrently perceivable referent: a bug on the ceiling. But is he doing the action of noticing and/or announcing? To solve this terminological analytic problem, Pillet-Shore (2008, 2017, 2018a, 2021) proposes the term “registering” to name the basic underlying social action (common to Excerpts (4)-(6)) of multimodally calling joint attention to a selected publicly perceivable referent so others shift their sensory (e.g., visual, auditory, olfactory) attention to it. In Excerpt (6), Ryan’s linguistic and embodied registering actions—including his utterance, gaze (Fig.6b), and body lean (Fig.6c)—observably occasion his coparticipants to suddenly shift their displayed visual attention to follow Ryan’s gaze to his selected, publicly perceivable referent (Fig.6c). (See Pillet-Shore [2021] for analysis of registering sequences, including how participants produce and understand their actions guided by a structural preference organization.)

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Dunbar, R. I. M. (2004). Gossip in evolutionary perspective. Review of General Psychology, 8(2), 100-106.

Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp. 97–121). New York, NY: Irvington Publishers.

Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (2012). Car talk: Integrating texts, bodies, and changing landscapes. Semiotica, 191(1/4), 257–286.

Heritage, J. (2012). The epistemic engine: Sequence organization and territories of knowledge. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 45(1), 30-52.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2008). Coming together: Creating and maintaining social relationships through the openings of face-to-face interactions. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2017). Preference organization. In Oxford research encyclopedia of communication, edited by J. Nussbaum. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2018a). How to begin. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(3):213–231.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2018b). Arriving: Expanding the personal state sequence. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(3):232–247.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2021). When to make the sensory social: Registering in face-to-face openings. Symbolic Interaction, 44(1), 10-39.

Sacks, H. (1975). Everyone has to lie. In M. Sanches and B. Blount (Eds.), Sociocultural dimensions of language use (pp. 64-79). New York: Academic Press.

Schegloff, E. A. (1996). Some practices for referring to persons in talk-in-interaction: A partial sketch of a systematics. In B. Fox (Ed.), Studies in anaphora (pp. 437-85). Amersterdam: John Benjamins.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A Primer in conversation analysis (Vol. 1). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Stivers, T. & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing response. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1):3–31.

Terasaki, A. K. (2004). Pre-announcement sequences in conversation. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 171–223). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Additional References: