Registering

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Registering | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Danielle Pillet-Shore (University of New Hampshire, USA) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4757-4082) |

| To cite: | Pillet-Shore, Danielle. (2023). Registering. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/ZUKAS |

Registering refers to the linguistic and embodied action of calling joint attention to a selected, publicly and concurrently perceivable referent so others shift their attention to it. As a sequence-initial/initiating action, registering projects the relevance of coparticipants’:

(i) displayed sensorial attention to, and shared awareness of, the target referent—including visible, audible, palpable, and olfactible features of the setting and its participants (Pillet-Shore, 2021; Schegloff, 2007:74, 82–88, 219); and

(ii) display of achieved “intersubjectivity” (Heritage, 1984:254–256; Scheff, 2005) by sharing their understandings of the local meaning and value of the target referent (Pillet-Shore, 2021:33).

Because the action of registering treats the target referent as its source, it can launch a “retro-sequence” (Schegloff, 2007:217-19). Registering is a pervasive social action that participants to interaction use to introduce a new topic/sequence of interaction, including during conversation openings (Pillet-Shore, 2008, 2018, 2021) and at a places of possible sequence completion (e.g., to resolve a lapse in conversation; Hoey, 2018).

Interaction studies use various terms to refer to this social action, including not only “registering” (e.g., Hoey, 2018; Pillet-Shore, 2008, 2017, 2018, 2021; Schegloff, 2007:87), but also “noticing” (e.g., Goodwin & Goodwin, 2012; Sacks, 1992 II:87-97; Schegloff, 1988:119-131, 2007), “announcing” (Schegloff, 2007:86-87; Stivers & Rossano, 2010:9), “setting talk” (Maynard & Zimmerman, 1984:304), “comments on the physical surroundings” (Keevallik, 2018), and “local sensitivity to elements in participants’ field of perception” (Bergmann, 1990:207). Observing that earlier studies’ use of various terms poses a problem for scientific consistency, Pillet-Shore (2021) argues that the term registering offers several advantages:

- it names an action-in-conversation that is intrinsically social (cf. to “noticing,” which names both a perceptual/cognitive event, and a social/interactional event; Schegloff, 2007:87);

- it embraces multimodal action designs and various referent types (cf. to “setting talk” [Maynard & Zimmerman, 1984], which focuses only on lexicalized utterances indexing inanimate, unowned referents); and

- it is comparatively parsimonious, naming the basic, underlying social action for what it is apparently designed to do, rather than varying the action name depending upon what the referent is, or which participant does it. Compare to Schegloff’s (2007:82) use of several terms, including “registering,” “noticing,” and “announcing”: “In achieving the official and explicit registering of some feature… affiliated to or identified with one of the participants—and ‘positively valued’ features in particular—there appears to be a preference for noticing-by-others over announcement-by-‘self’ (where ‘self’ is the one characterized by the feature).” Pillet-Shore (2021) conceptualizes registering as encompassing earlier CA works’ notions of both “noticing” and “announcing” a here-and-now referent, showing it to be a useful analytic term, including when participants call joint attention to a target referent in a way that resists neat and defensible categorization as either “noticing” or “announcing,” as in Excerpt (1) at line 3:

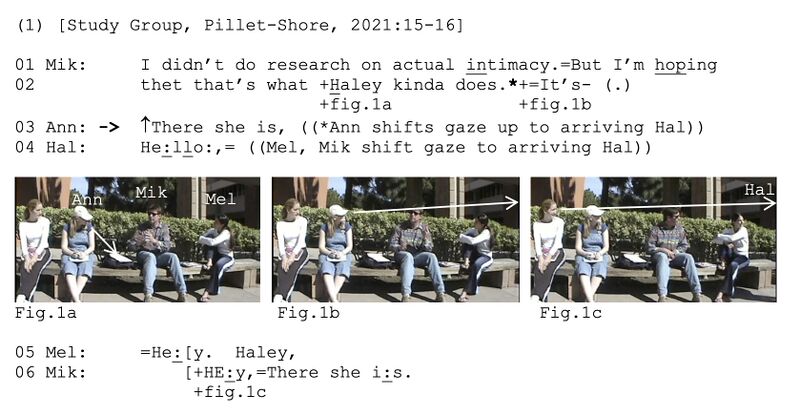

During Mike’s utterance at line 2 (at *; see Fig.1b), Ann does a sudden gaze shift up toward the arriving newcomer Haley—an apparent initial sighting that directly precedes and engenders line 3. Applying an earlier study (e.g., Goodwin & Goodwin, 2012:276-277), it is plausible that Ann is “noticing” Haley’s arrival because she uses a deictic term, appears to have just spotted a newly visible referent, and audibly uses discovery prosody (cf. Goodwin, 1979). At the same time, it is also plausible that Ann is “announcing” Haley’s arrival, since it is a declarative utterance produced by a speaker displaying a knowing epistemic stance (she does not display an unknowing-to-now-knowing epistemic stance via turn-initial reaction token; Heritage 1984:286–7), and Ann uses a third-person reference form to refer to the arriver, thereby addressing her utterance to already-present and situated others as an intended informing. As a way past this terminological ambiguity, Pillet-Shore (2021:15-16) observes that Ann’s utterance and sudden gaze shift accomplish the more basic underlying social action of “registering”—calling joint attention to, and occasioning her coparticipants to shift their gaze/attention and shared awareness to—Ann’s selected, publicly perceivable target referent (Fig.1c).

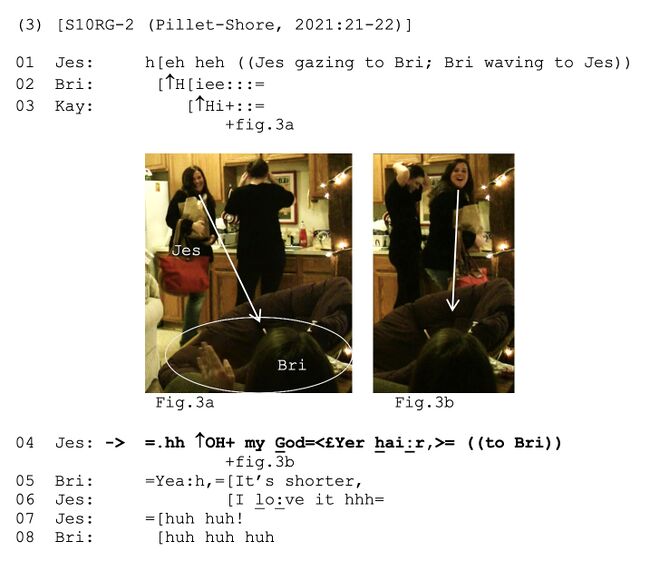

Participants to interaction use various multimodal (visible and/or audible) resources and design formats to do sequence-initial registering actions (Pillet-Shore, 2021:18). These include embodied actions (e.g., sudden gaze shifts, such as doing a double-take while gazing at the target referent with a stance-displaying facial expression as in Excerpt (3)-Figures 3a and 3b; or directed gaze + laughter/object showing), and spoken utterances that audibly point (Pillet-Shore, 2021:11-12) to a selected target referent (e.g., using deictic terms and perceptual directives [Goodwin & Goodwin, 2012:275-279]). Registering utterances may be produced as positive or negative observations (cf. Schegloff, 1988), with declarative or interrogative grammar, and with or without evidential verbs (Chafe & Nichols, 1986), reaction tokens (cf. Wilkinson & Kitzinger, 2006), and/or an explicated stance toward the target referent.

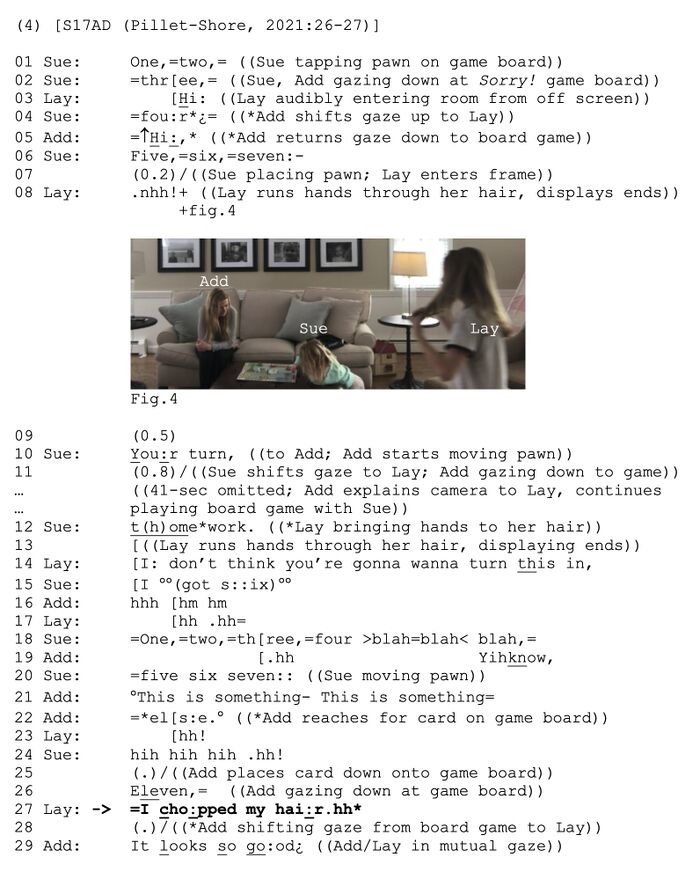

As one way of making reference in interaction (cf. Enfield, 2013), registering involves selecting a target referent from among a vast number of perceivable stimuli. People can register referents that are either owned (oriented to as some participant’s responsibility; e.g., how a person looks/smells; how a person’s residence looks/smells; Pillet-Shore, 2021; cf. Schegloff, 2007:82), or unowned (not oriented to as a participant’s responsibility; e.g., the weather; for review, see Keevallik, 2018). The bolded utterances in Excerpts (2), (3) and (4) show participants registering an owned referent by calling joint attention to a participant’s new hairstyle:

Pillet-Shore (2021) argues that analyzing the basic underlying social action of registering enables the detection of a systematic structural preference organization to which participants observably orient when calling joint attention to an owned referent. For example, non-owners displaying a positive stance toward the target referent produce registering ‘yours’ actions (as exemplified in Excerpts (2) and (3)) with “preferred” design—i.e., sooner, close to initial perceptual exposure (Schegloff, 2007:86) and at the earliest moment in the interaction when that registering action may be initially relevantly performed (cf. Pillet-Shore, 2018). Owners of a potentially praiseable target referent, however, produce registering ‘mine’ actions (as exemplified in Excerpt (4)) with “dispreferred” design—i.e., later, delayed relative to points in the interaction when that registering action might otherwise have been initially relevantly performed (Pillet-Shore, 2017, 2021; cf. Robinson & Bolden, 2010:503). In Excerpt (4), the owner of the target referent, Layla, observably delays her registering utterance (at line 27) relative to her nanny Addison’s initial perceptual exposure (during line 4) and relative to earlier points in their opening when Addison might have relevantly registered her hair cut (including when Layla displays her hair’s freshly cut ends at line 8/Fig.4 and lines 12-13; for full analysis, see Pillet-Shore [2021:25-27]). This study concludes that interactants use the social action of registering an owned referent as a vehicle for doing other stance-implicative actions, including complimenting, self-deprecating to preempt a fellow participant’s potential criticism, fishing for another’s praise, or implicitly criticizing a fellow participant (Pillet-Shore, 2021:34).

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Bergmann, J. (1990). On the local sensitivity of conversation. In I. Markova and K. Foppa (Eds.), The dynamics of dialogue (pp. 201–282). Hertfordshire, UK: Harvester.

Chafe, W. L. & Nichols, J. (eds.). (1986). Evidentiality: The linguistic coding of epistemology. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Enfield, N. J. (2013). Reference in conversation. In J. Sidnell and T. Stivers (Eds.), The Handbook of Conversation Analysis (pp. 433–454). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Goodwin, C. (1979). The interactive construction of a sentence in natural conversation. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday language: Studies in ethnomethodology (pp. 97–121). New York, NY: Irvington Publishers.

Goodwin, C., & Goodwin, M. H. (2012). Car talk: Integrating texts, bodies, and changing landscapes. Semiotica, 191(1/4), 257–286.

Heritage, J. (1984). Garfinkel and ethnomethodology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Hoey, E. (2018). How speakers continue with talk after a lapse in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(3):329–346.

Keevallik, L. (2018). Sequence initiation or self-talk? Commenting on the surroundings while mucking out a sheep stable. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(3):313–328.

Maynard, D. W. & Zimmerman, D. H. (1984). Topical talk, ritual and the social organization of relationships. Social Psychology Quarterly, 47(4):301–316.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2008). Coming together: Creating and maintaining social relationships through the openings of face-to-face interactions. Ph.D. dissertation. Department of Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2017). Preference organization. In Oxford research encyclopedia of communication, edited by J. Nussbaum. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2018). How to begin. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(3):213–231.

Pillet-Shore, D. (2021). When to make the sensory social: Registering in face-to-face openings. Symbolic Interaction, 44(1), 10-39.

Robinson, J. & Bolden, G. (2010). Preference organization of sequence-initiating actions: The case of explicit account solicitations. Discourse Studies, 12(4): 501-533.

Scheff, T. (2005). Looking-glass self: Goffman as symbolic interactionist. Symbolic Interaction, 28(2):147–166.

Schegloff, E. A. (1988). Goffman and the analysis of conversation. In P. Drew and A. J. Wootton (Eds.), Erving Goffman: Exploring the interaction order (pp. 89-135). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A Primer in conversation analysis (Vol. 1). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Stivers, T. & Rossano, F. (2010). Mobilizing response. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 43(1):3–31.

Wilkinson, S. & Kitzinger, C. (2006). Surprise as an interactional achievement: Reaction tokens in conversation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69(2):150–182.

Additional References:

Kidwell, M. & Zimmerman, D. H. (2007). Joint attention as action. Journal of Pragmatics, 39:592–611.