Sound object

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Sound object | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Elisabeth Reber (University of Hildesheim, Germany) |

| To cite: | Reber, Elisabeth. (2024). Sound object. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/ABVR5 |

A sound object (Reber 2009, 2012; Reber & Couper-Kuhlen 2010) is an interactional object with phonetic substance but minimal semantic content. It “[evokes] prismatic meaning clusters which are methodically left unstated by participants” (Reber 2012: 245). Sound objects comprise words, specifically primary interjections, e.g., the variants of English oh, ah, and wow, German / French pf / pff, as well as “non-lexical sounds” (Reber 2012: 12, my emphasis) or “non-lexical vocal tract sounds” (Reber & Couper-Kuhlen 2020: 164, my emphasis) across languages, e.g., clicks, whistling, sighing, and lip smacks, with the boundaries between lexical and non-lexical structures being potentially fuzzy (Baldauf-Quilliâtre & Imo 2020; Hoey 2014, 2020; Reber 2012, Reber & Couper-Kuhlen 2020; Wiggins & Keevallik 2021).

The study of sound objects extends the prior work on “vocalizations” (Goffman 1978) which has shown that primary interjections and non-lexical sounds are deployed in a systematic, situated fashion with respect to their sequential organization (Schegloff 1982). The term sound object highlights the observation that vocalizations may additionally be produced with a systematic, situated prosodic-phonetic packaging, thus “reflect[ing] the fact that these objects are spoken language resources for which the sound pattern and its context-specific use are distinctive for the meaning” (Reber 2012: 12). Sound objects are vocalizations characterized by recurrent patterns of form and function. They can implement initiating actions, e.g., tonal whistles can be used for the summoning of human participants and domestic animals (Reber & Couper-Kuhlen 2020), and responsive actions, e.g., extra high and pointed oh can be deployed as ‘surprised’ repair receipt (Reber 2012). Sound objects can also serve other interactional relevancies, e.g., the management of speakership by “buy[ing] time in spaces where speakership is unclear” (Hoey 2014: 192). The production of sound objects may also involve recurrent bodily movements (Wiggins & Keevallik 2021). Responsive sound objects constitute a type of minimal response, along with, e.g., nonverbal responses such as nodding.

Interjections have been treated as a grammatical word class prototypically associated with spontaneous expressions of emotion and anomalous phonology, and often sidelined by linguistic grammars due to their lack of syntactic functions within sentence structure (Jespersen 1922, 1924; Quirk et al. 1985; but see Biber et al. 1999). The term sound object intends to reframe interjections as indexical, orderly linguistic signs. For these signs, the sound patterns and sequential positioning are distinctive for their meaning-making and functions in social interaction. The term is more inclusive than interjection by comprising lexical and non-lexical tokens. It recognizes that interjections and non-lexical sounds may share similar sequential positions as well as interactional and social functions. In the conversation analytic / interactional linguistic literature on English, interjections tend to be treated as one type of particle (e.g., Heritage 1984; Thompson et al. 2015) but this classification is controversial (e.g., Ameka 1992).

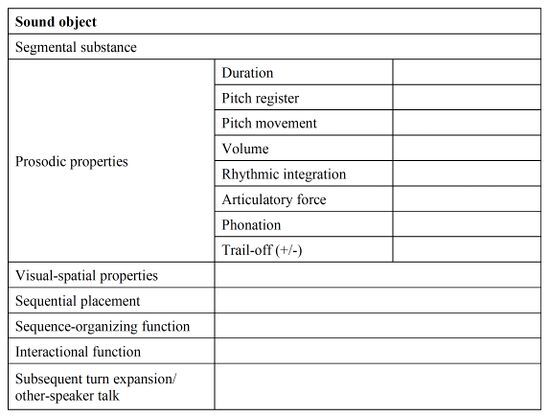

Reber & Couper-Kuhlen (2010) propose a scheme for the analysis of sound objects based on their empirical findings (Table 1). It illustrates that the form of sound objects is multifaceted and not only defined by their phonetic substance (as conveyed by dictionaries) nor intonation (e.g., Norrick 2014: 250). Not all of these features may be characteristic of sound objects all the time: For instance, clicks tend not to have prosodic prominence. The role of visual-spatial properties is understudied.

Table 1: Scheme for the analysis of sound objects (Reber & Couper-Kuhlen 2010: 88; my translation, ER)

The following extract (1), adapted from Reber (2012: 201-202), illustrates the patterned use of the sound object ‘low-falling and tailed’ ah (line 23).

(1) [HOLT:M88:2:] "wretched gout" (Reber 2012: 201-202, adapted)

Formal features:

- Segmental substance: vowel quality close to cardinal vowel 5

- Prosodic properties: lengthened duration, low pitch register; pitch movement beginning in the mid range of the speaker’s voice and falling on a glide to the lower range, ending as a level

- Articulatory force: stronger than that of ‘flat-falling and low ah’.

- Phonation: sometimes aspirated

- Sequential placement:

- A: enquiry about mental / physical state of the recipient or a third party (line 14)

- B: announcement of bad news (line 22)

- A: affect-laden bad-news receipt (low-falling and tailed ah, line 23)

Functional features:

- Interactional function: displays sympathy with the consequential figure of the bad news, Geoff

- Sequence-organizing function: acknowledgement of bad news, potentially sequence terminating (bad-news response)

Turn expansion:

- Idiomatic expressions of ‘sympathy’ (pOO:r GEOFF, line 24)

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Ameka, F. (1992). The meaning of phatic and conative interjections. Journal of Pragmatics, 18, 245–271.

Baldauf- Quilliâtre, H. & Imo W. (2020). Pff. In Imo, W. & Lanwer, J. P. (Eds.), Prosodie und Konstruktionsgrammatik (pp. 201–232). de Gruyter.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S. & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Longman.

Goffman, E. (1978). Response cries. Language, 54, 787–815.

Heritage, J. (1984). A change-of-state-token and aspects of its sequential placement. In Atkinson, J. M. & Heritage, J. (Eds), Structures of Social Action. Studies in Conversation Analysi (pp. 299–345). Cambridge University Press.

Hoey, E. M. (2014). Sighing in interaction: Somatic, semiotic, and social. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 47, 175–200.

Hoey, E.M. (2020). Waiting to inhale. Sniffing in conversation. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53, 118–139.

Jespersen, O. (1922). Language. Its nature, development and origin. Allen and Unwin.

Jespersen, O. (1924). The Philosophy of Grammar. Allen and Unwin.

Norrick, N. (2014). Interjections. In K. Aijmer & Rühlemann, C. (Eds.), Corpus Pragmatics: A Handbook (pp. 249-276). Cambridge University Press.

Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G. & Svartvik, J. (1985). A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. Longman.

Reber, E. (2009) Zur Affektivität in englischen Alltagsgesprächen. In M. Buss, Habscheid, St., Jautz, S. Liedtke, F. & Schneider, J. G. (Eds.), Theatralität des sprachlichen Handelns. Eine Metaphorik zwischen Linguistik und Kulturwissenschaften (pp. 193–215). Fink-Verlag.

Reber, E. (2012). Affectivity in Interaction: Sound objects in English. John Benjamins.

Reber, E. & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2010). Interjektionen zwischen Lexikon und Vokalität: Lexem oder Lautobjekt? In Deppermann A. & Linke, A. (Eds.), Sprache intermedial: Stimme und Schrift, Bild und Ton (pp. 69–96). de Gruyter.

Reber, E. & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2020). On ‘whistle‘ sound objects in English everyday conversation. Special Issue ‘Sounds on the Margins of Language’ (L. Keevallik & R. Ogden, eds) Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53, 164–187.

Schegloff, E. (1982). Discourse as an interactional achievement: some uses of ‘uh huh’ and other things that come between sentences. In Tannen, D. (Ed.), Analyzing Discourse: Text and talk (pp. 71–93). Georgetown University Press.

Thompson, S. A., Fox, B. A. & Couper-Kuhlen, E. (2015). Grammar in Everyday Talk: Building responsive actions. Cambridge University Press.

Wiggins, S. & Keevallik, L. (2021). Parental lip-smacks during infant mealtimes. Multimodal features and social functions. Interactional Linguistics, 1, 241–272.

Additional References:

Baldauf-Quilliâtre, H. (2016). ‘pf’ indicating a change in orientation in French interactions. Journal of Pragmatics, 104, 89–107.

Barth-Weingarten, D. (2011). Response tokens in interaction – prosody, phonetics and a visual aspect of German JAJA. Gesprächsforschung – Online-Zeitschrift zur verbalen Interaktion, 12, 301–370.

Barth-Weingarten, D., Couper-Kuhlen, E. & Deppermann, A. (2020). Konstruktionsgrammatik und Prosodie: OH in englischer Alltagsinteraktion. In Imo, W.& Lanwer, J. P. (Eds.), Prosodie und Konstruktionsgrammatik (pp. 35–73). de Gruyter.

Imo, W. & Lanwer, J. P. Prosodie und Konstruktionsgrammatik. In Imo, W. & Lanwer, J. P. (Eds.), Prosodie und Konstruktionsgrammatik (pp. 1–33). de Gruyter.

Kupetz, M. (2014). Empathy displays as interactional achievements – Multimodal and sequential aspects. Journal of Pragmatics, 61, 4–34.

Keevallik, L. & Ogden, R. (2020). Sounds on the margins of language at the heart of interaction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 53, 1–18.

Reber, E. (2020). Interjektionen – an den Rändern der Sprache? In Elmentaler, M. & Niebuhr, O. (Eds.), An den Rändern der Sprache (pp. 39–65). Peter Lang.

Tissot, F. 2015. Gemeinsamkeit schaffen in der Interaktion: Diskursmarker und Lautelemente in zürichdeutschen Erzählsequenzen. Peter Lang.