Multimodal transcription

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Multimodal transcription | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Lorenza Mondada (University of Basel, Switzerland) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7543-9769) |

| To cite: | Mondada, Lorenza. (2024). Multimodal transcription. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/8U3NX |

A multimodal transcription is a form of annotation of the multimodal resources organizing social interaction, including language, prosody, gesture, gaze, head movements and facial expressions, body postures, movements in space, and manipulations of objects. ‘Transcription’ refers both to the action producing it (transcribing) and to its final product (transcript).

As a fundamental practice within CA, the process of transcribing follows several analytic requirements. These requirements include in particular the relevance of detail, the notion of order at all points, the importance of the question “why that now?” for the participants, the centrality of temporality, and sequentiality. Transcribing is an embodied practice involving specific forms of professional looking and listening that are technologically supported (media players for listening and viewing, software for transcribing, software for aligning annotations with the audio-visual signal, etc.). Transcribing has the paradoxical properties of inscribing spoken words in a textual form, of spatializing time, and of stabilizing dynamic flows (Bergmann, 1985).

Multimodal transcription is different from verbal and vocal transcription in several ways. Whereas verbal/vocal transcripts often follow a standard procedure with shared conventions (Jefferson, 1995, 2004; Hepburn & Bolden, 2012), multimodal transcripts are still characterized by a variety of practices. Moreover, whereas the former are based on (adapted) orthographic conventions specific to written norms, which linearize and segment talk in recognizable units, the latter cannot appeal to a similar tradition for the notation of embodied conduct, which rather represents a continuous and gradual flow of actions. And whereas it is possible to produce a relatively homogeneous, basic transcript for an entire recording of talk, it is almost impossible to do the same for a multimodal transcription of a video recording.

Multimodal transcripts remind one that transcribing is always a selective activity (as it is for talk), depending on the objectives and granularity of the analysis, the recipient-oriented/reader-friendly character of the final version, and so on. Although selectivity can vary depending on the analytical focus, as well as on editorial requirements and rhetorical strategies, it ultimately depends on the central issue of relevance (Sacks, 1992; Schegloff, 2007). The relevance of resources is locally achieved and established by the participants themselves in and for their situated action, exploiting and orienting to them as publicly available, meaningful, and providing the accountability of their actions. This constitutes the fundamental emic dimension of multimodal transcription, consistent with the emic view on language, action, and social interaction characteristic of CA. The relevance of details is always indexical; it cannot be decided a priori and once and for all—and this distinguishes the practice of transcribing from the practice of coding.

Within CA there are several conventions for transcribing: Goodwin’s (1981) convention for gaze, Heath’s musical score representations (see Luff & Heath, 2015 for a recent account), Laurier’s comic book stylization (2014), and Mondada’s (2018) conventions, which are not limited to particular types of phenomena but are adaptable to a diversity of embodied conducts, and are particularly careful in preserving and highlighting their finely detailed temporal orders.

Multimodal annotations deal with two fundamental aspects of embodied conduct—which are not limited to gesture or gaze, but concern all kinds of bodily movement—(a) their temporality (i.e., their emergent and unfolding trajectory, including preparation and retraction, precisely situated within the turn and the action); and (b) their shape (i.e., what makes the movement recognizable and describable). The latter aspect raises the practical and analytical question of how to describe these movements, with the aim of relevantly capturing what the person is doing and what the coparticipant(s) can see her/him doing, within their emic perspective. Moreover, these descriptions are implemented not only in textual form but also in iconic form, namely, the screenshots/figures. The analyst decides how to distribute these descriptions between transcript, images, and the analytical text. In this sense, glosses in the transcript are shorthand for something that is elaborated elsewhere; in turn, the specific information the transcript provides concerns the temporal details, positions, trajectories, and arrangements of the movements. Both aspects of temporality and shape are necessary to understand what the body is doing. Within this conception of multimodality, the meaning of a movement is not reducible to its form but is related to the moment in which it is produced; a moment that is meaningful in relation to its sequential environment and its position within the ongoing action.

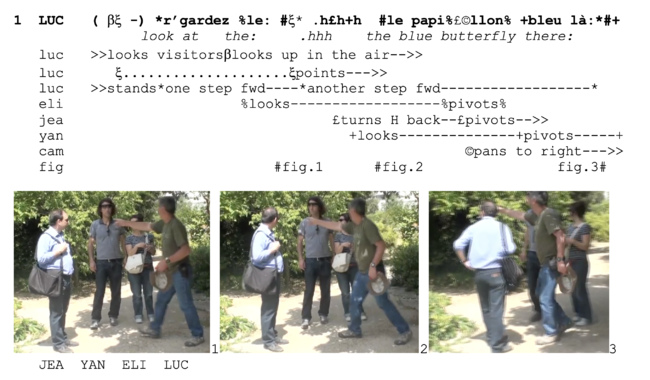

The following is an example of transcription adopting Mondada’s (2018) conventions (for the transcription of silences see Mondada 2019; for transcriptions of non-human animals see Mondémé, 2020 and Mondada & Meguerditchian, 2022). The extract shows a noticing produced by a gardener (Luc), while he guides some visitors (Yan, Elise, and Jean) through his garden and points at various vegetal and animal details (see Mondada, 2014a for more systematic analyses)

[papillon bleu] (Mondada 2014a)

Luc utters his turn while bodily orienting towards the butterfly he just noticed and which has occasioned an abrupt suspension of his previous talk (see the beginning of line 1). His embodied orientation involves gaze, manual gesture, and trunk movements. As soon as he spots the butterfly, he moves his gaze from the visitors he was addressing until then, and looks in the air, beginning to point (… indicates the emergent expansion of his pointing, until the gesture is fully expanded). His standing is also transformed by the noticing: he was immobile in front of the visitors and now he steps forward in direction of the butterfly (Figure 1). In this way, he is not merely pointing, but his entire body becomes tensed towards the object pointed at (Figure 2). The multimodal transcription shows these multiple layers, as they make sense together, despite having specific temporalities (sight moves first, then the arm/hand/fingers, and finally the entire body stepping forward). The quality of this multimodal Gestalt is analytically described by these various layers but is also holistically represented by the emergent movement of the entire body visible in the images (Figures 1-3).

However, the multimodal transcription does not only represent the multiple temporalities of the speaker’s multilayered linguistic and embodied action; it also addresses the ways it is responded to. Embodied responses generally do not wait for the completion of the turn—as verbal responses often do. They may begin as the previous action is unfolding. In our case, Elise is the first to turn her head towards the pointed at direction (Figure 1), followed by Jean and Yan at almost the same moment. The participants first turn their heads for looking; then the prolongation of their look involves their entire bodies (including legs and feet), since they pivot towards the pointed at direction. This produces an emergent collective movement transforming the interactional space, initially focused on Luc and now oriented towards the putative butterfly. The cameraperson participates to this movement, since the camera moves too—relatively late. This is integrated in the multimodal transcript, which treats the cameraperson as another participant (Mondada, 2016) and in some cases becomes the phenomenon of analysis (Mondada, 2014b).

Furthermore, the action of the recipients is not merely responsive to the action of the speaker: both are reflexively tied, mutually shaping each other. This is visible in the temporal details of the transcript: we can observe that in the short time between Elisa’s look and the other recipients’ look, Luc’s turn is characterized by some hitches ("le: .hhh le papillon", line 1). These discontinuities and self-repairs manifest a temporal and micro-sequential adjustment of Luc to the timing of his co-participants’ responses. He then continues (without any hitches) as soon as all the co-participants have turned to the pointed at direction. In this way Luc’s turn both shapes the responses and is shaped by them. The multimodal transcription and its precise rigorous temporality enable us to demonstrate this reflexive shaping of the turn and its response (cf. already Goodwin, 1981).

The relevant multimodal details, once transcribed, are made available for the analysis and for its substantiation: they constitute the evidence on which the analysis is based. The transcript and the analysis mutually inform each other, since the transcription enables and even imposes, but also is produced by a specific form of analytical viewing of the video record. The proto-analytical viewing of the video record is consigned in transcribing, and the transcript is progressively expanded, specified, and enriched on the basis of multiple viewings and further transcribing.

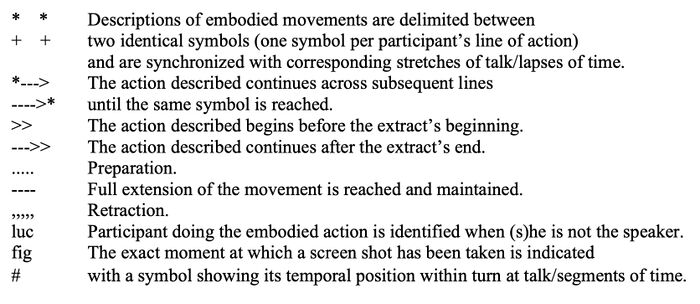

Conventions:

Below is a short version of the multimodal conventions proposed by Mondada (2018); for a complete version see Mondada’s website.

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Bergmann, J. (1985). Flüchtigkeit und methodische Fixierung sozialer Wirklichkeit: Aufzeichnungen als Daten der interpretativen Soziologie. In W. Bonss & H. Hartmann (eds.), Entzauberte Wissenschaft (pp. 299-320). Schwarz.

Goodwin, C. (1981). Conversational organization: Interaction between speakers and hearers. Academic Press.

Hepburn, A. & Bolden, G. B. (2012). The conversation analytic approach to transcription. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (eds.) The handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 57-76). Blackwell.

Jefferson, G. (1985). An exercise in the transcription and analysis of laughter. In T. A. van Dijk (ed.), Handbook of discourse analysis volume 3 (pp. 25-34). Academic Press.

Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (ed.) Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13-34). John Benjamins.

Laurier, E. (2014). The graphic transcript. Geography Compass, 8(4), 235-248.

Luff, P., & Heath, C. (2015). Transcribing embodied action. In D. Tannen, H. E. Hamilton, & D. Schiffrin (eds.), The handbook of discourse analysis (pp. 367-390). Wiley.

Mondada, L. (2014a). Pointing, talk and the bodies: Reference and joint attention as embodied interactional achievements. In M. Seyfeddinipur, & M. Gullberg (eds.), From gesture in conversation to visible utterance in action (pp. 95-124). John Benjamins.

Mondada, L. (2014b). Shooting as a research activity: The embodied production of video data. In M. Broth, E. Laurier, & L. Mondada (eds.), Video at work (pp. 33-62). Routledge.

Mondada, L. (2016). Challenges of multimodality: Language and the body in social interaction. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 20(2), 336-366.

Mondada, L. (2018). Multiple temporalities of language and body in interaction: Challenges for transcribing multimodality. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 51(1), 85-106.

Mondada, L. (2019). Transcribing silent actions: A multimodal approach of sequence organization. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality, 2(2).

Mondada, L. (accessed 29.11.2022). Multimodal transcription conventions and Tutorial for implementing them. https://franz.unibas.ch/fileadmin/franz/user_upload/redaktion/Mondada_conv_multimodality.pdf)

Mondada, L., & Meguerditchian, A. (2022). Sequence organization and embodied mutual orientations: Openings of social interactions between baboons. Philisophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 377, 20210101.

Mondémé, C. (2020). Touching and petting: exploring “haptic sociality” in interspecies interaction. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (eds.), Touch in social interaction: Touch, language, and body (pp. 171-196). Routledge.

Sacks, H. (1992). Lectures on conversation. Blackwell.

Schegloff, E. A. (2007). Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Additional References:

Ayass, R. (2015). Doing data: the status of transcripts in Conversation Analysis. Discourse Studies, 17(5), 505-528.

Bucholtz, M. (2000). The politics of transcription. Journal of Pragmatics, 32(10), 1439-1465.

Kendon, A. (1977). Studies in the Behavior of Face-to-Face Interaction. Peter De Ridder Press.

Mondada, L. (2016). Zwischen Text und Bild: Multimodale Transkription. In H. Hausendorf, R. Schmitt and W. Kesselheim (eds.) Interaktionsarchitektur, Sozialtopograhie und Interaktionsraum (pp. 111-160). Narr.

Ochs, E. (1979). Transcription as theory. In E. Ochs and B. Schieffelin (eds.) Developmental Pragmatics (pp. 43-72). Academic Press.