Difference between revisions of "Affect"

ChaseRaymond (talk | contribs) |

ChaseRaymond (talk | contribs) |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox cite | {{Infobox cite | ||

| Authors = '''Julia Katila''' (Tampere University, Finland), '''Juhana Mustakallio''' (Tampere University, Finland) (https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3187-7849), and '''Johanna Ruusuvuori''' (Tampere University, Finland) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4802-0081) | | Authors = '''Julia Katila''' (Tampere University, Finland), '''Juhana Mustakallio''' (Tampere University, Finland) (https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3187-7849), and '''Johanna Ruusuvuori''' (Tampere University, Finland) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4802-0081) | ||

| − | | To cite = Katila, Julia, Juhana Mustakallio, & Johanna Ruusuvuori. (2024). Affect. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), ''Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics''. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: [ ] | + | | To cite = Katila, Julia, Juhana Mustakallio, & Johanna Ruusuvuori. (2024). Affect. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), ''Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics''. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: [http://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/AZFWY 10.17605/OSF.IO/AZFWY] |

}} | }} | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

'''Additional Related Entries:''' | '''Additional Related Entries:''' | ||

| + | * '''[[Affective stance]]''' | ||

* '''[[Affiliation]]''' | * '''[[Affiliation]]''' | ||

* '''[[Alignment]]''' | * '''[[Alignment]]''' | ||

Latest revision as of 19:03, 16 September 2024

| Encyclopedia of Terminology for CA and IL: Affect | |

|---|---|

| Author(s): | Julia Katila (Tampere University, Finland), Juhana Mustakallio (Tampere University, Finland) (https://orcid.org/0009-0004-3187-7849), and Johanna Ruusuvuori (Tampere University, Finland) (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4802-0081) |

| To cite: | Katila, Julia, Juhana Mustakallio, & Johanna Ruusuvuori. (2024). Affect. In Alexandra Gubina, Elliott M. Hoey & Chase Wesley Raymond (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Terminology for Conversation Analysis and Interactional Linguistics. International Society for Conversation Analysis (ISCA). DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/AZFWY |

Emotions and affects are an omnipresent aspect of all interaction, but they are rarely explicated in words. In conversation analysis the terms ‘emotion’ and ‘affect’ are used often interchangeably to refer to observable aspects of sentiments emerging in and through interaction (Ruusuvuori 2013: 332). A distinct feature about the treatment of emotion and affect in the field of conversation analysis is that emotion and affect are regarded as social signals instead of, for instance, individual experiences (see Hochschild 1979). Thus, rather than investigating emotions or affect per se (Ruusuvuori 2013: 332), they are treated as “situated practices” (Goodwin & Goodwin 2000; Goodwin et al. 2012) emerging through moment by moment unfolding interaction resources, such as laughter (Jefferson 1979).

Current perspectives within conversation analysis have highlighted the multisensorial aspect of emotion and affect: They unfold through the co-production of multiple senses and modalities, including touch, prosody, facial expressions and the body (Cekaite & Kvist Holm 2017; Goodwin 2007; M.H. Goodwin 2017; Goodwin & Cekaite 2018; Ruusuvuori & Peräkylä 2009). Drawing from the work of Merleau-Ponty (1962), intercorporeal perspectives (see Meyer et al. 2017) have focused on the embodied and corporeally shared aspects of emotion and affect in interaction (M.H. Goodwin 2017; Katila & Raudaskoski 2020; Katila & Turja 2021).

Conversation analysis cannot access how emotions and affect are felt by the participants as such. Instead, through detailed analysis of multisensorial and embodied actions, it uncovers how the participants display, produce, and make available emotions and affect through various multimodal and -sensorial resources. In example (1), the participants are not expressing emotions and affect in words. Rather, they are making their emotions and affect observable in and through various types of embodied displays. The patient, an 8-year-old with a fear of the dentist, has just been given a local anesthesia injection. As the patient makes their pain reaction available to other people through loud crying (line 01) and facial expressions indicating discomfort (Figure 1), the dentist responds to this affective display with an empathetic touch to the patient’s cheek (Figure 1). At the same time the dentist asks, with a gentle tone of voice, if the patient has a bad taste in their mouth (line 02).

(1)

01 Patient: AAA AAA AAA AAAA AAAA ((crying))

02 Dentist: onko pahaa (Figure 1) makua suussa

'do you have a bad (Figure 1) taste in your mouth'

Figure 1

Figure 1

In example (1), emotion and affect are embedded in embodied behavior. The patient is making their feeling body interactionally available to others with a combination of vocal and visual signs. As a response, empathy is displayed to the patient through comforting touch and gentle prosody. Example (1) thus demonstrates the multisensorial and intercorporeal aspect of emotion and affect displays. The corporeal act of crying is attended to by the corporeal act of touch, and this is mediated across the participants’ bodies through direct embodied connection.

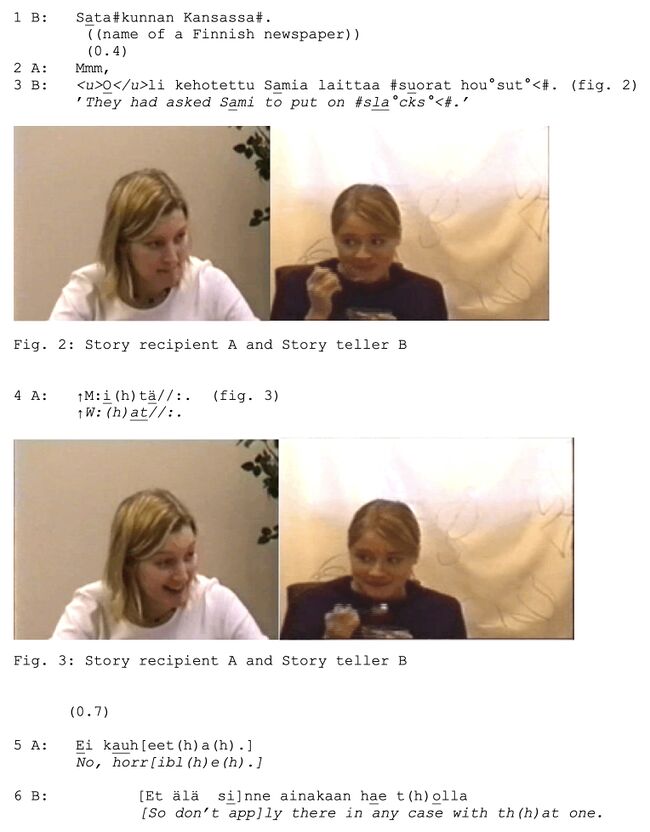

Example (2) contrasts with the first in its affective quality. We show how affects are used in creating positive atmosphere and creating alignment with verbal and non-verbal resources. It is from a Finnish dataset of lunch conversations between students. Before the example, there has been a slight conflict and a longish silence after which B begins a storytelling sequence to reconcile and lighten the mood. The example shows how affect and emotion are intertwined in interactive sequences such as jocular storytelling where laughter and smiling emerges.

(2) (Peräkylä & Ruusuvuori 2009)

The storyteller B tells about a friend “Sami”, who had been asked to wear slacks at their workplace, a Finnish newspaper called “Satakunnan Kansa”. B constructs their strory as a joke using various embodied means, including smile, gaze and posture. In line 3 and Figure 2, B gazes at the story-recipient A, and delivers the end of the punchline (“slacks”, line 3). Simultaneously, B begins a widening smile that grows greater when A delivers a surprised answer “↑W:(h)at//:.” (line 4) said with a smiling face (Figure 2). A then continues appreciating the strory and produce it as laughable with assessement “No, hor[rib(h)ble(h).”, reciprocal smile and laughter (line 5). This way, she appropriately aligns with B’s affective stance. Furthermore, both participants produce their sentences with laugh tokens after the punchline (lines 5,6). By doing so they are collaboratively creating the affective atmosphere as positive, and marking the story as humorous.

One emerging theme in studying emotion and affect as situated practices is the relation between interactional displays and individual experience. CA studies have paid increasing attention to phenomena such as emotion regulation (Peräkylä & Ruusuvuori 2012; Merlino 2021), psychophysiological reactions and affects (Peräkylä et al. 2016; Stevanovic et al. 2019) or management of affect displays (Robles, DiDomenico & Raclaw 2021; Weatherall 2021) in interaction. Studies on interaction among children (e.g., Kidwell 2011) and multisensorial interaction in close relationships (e.g., Katila & Raudaskoski 2020; Mondada 2020) have increased the interest towards this intertwine, illuminating the possibilities and methodological challenges it may bring to conversation-analytic research.

Additional Related Entries:

Cited References:

Cekaite, A., & Kvist Holm, M. (2017). The comforting touch: Tactile intimacy and talk in managing children’s distress. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 50(2), 109–127.

Goodwin, C. (2007). Participation, stance, and affect in the organization of activities. Discourse & Society, 18(1), 53–73.

Goodwin, M.H. 2017. Haptic Sociality: The Embodied Interactive Construction of Intimacy Through Touch’. In C. Meyer, J. Streeck & J. Scott Jordan (Eds.), Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction (pp. 73–102). Oxford University Press.

Goodwin, M.H., & Goodwin, C. (2000). Emotion within Situated Activity. In A. Duranti (Ed.), Linguistic Anthropology: A Reader (pp. 239–257). Blackwell.

Goodwin, M.H., Cekaite, A., & Goodwin, C. (2012). Emotion as Stance. In Marja-Leena Sorjonen & Anssi Peräkylä (Eds.), Emotion in Interaction (pp. 16–41). Oxford University Press.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575.

Jefferson, G. (1979), A technique for inviting laughter and its subsequent acceptance/declination. In G. Psathas (Ed.), Everyday Language: Studies in Ethnomethodology; (pp. 79–96.). Irvington.

Katila, J., & Raudaskoski, S. (2020). Interaction Analysis as an Embodied and Interactive Process: Multimodal, Co-operative, and Intercorporeal Ways of Seeing Video Data as Complementary Professional Visions. Human Studies 43, 445–470.

Katila, J., & Turja, T. (2021). Capturing the Nurse’s Kinesthetic Experience of Wearing an Exoskeleton: The Benefits of Using Intercorporeal Perspective to Video Analysis. Social Interaction. Video-Based Studies of Human Sociality 4.3.

Kidwell, M. (2020). Epistemics and embodiment in the interactions of very young children. In T. Stivers, L. Mondada, & J. Steensig (Eds.), The morality of knowledge in conversation (pp. 257–284). Cambridge University Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge.

Meyer, C., Streeck, J. & Scott Jordan, J. (2017). Introduction. In C. Meyer, J. Streeck, & J. Scott Jordan (Eds.), Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction (pp. xiv–xlix). Oxford University Press.

Merlino, S. (2021). Haptics and emotions in speech and language therapy sessions for people with post-stroke aphasia. In J.S. Robles & A. Weatherall (Eds.), How Emotions are Made in Talk (pp. 233–262). John Benjamins.

Mondada, L., Monteiro, D. & Tekin, B.S. (2020). The Tactility and Visibility of Kissing. Intercorporeal configurations of kissing bodies in family photography sessions. In A. Cekaite & L. Mondada (Eds.), Touch in Social Interaction: Touch, Language, and Body (pp. 54–80). Taylor and Francis.

Peräkylä, A., Voutilainen, L., Henttonen, P., Kahri, M., Stevanovic, M., Sams, M., & Rajava, N. (2016). Tarinankerronnan psykofysiologiaa. Sosiologia. Vol. 3.

Peräkylä, A., & Ruusuvuori, J. (2012). Facial expression and interactional regulation of emotion. In Peräkylä, A. & Sorjonen, M.-L. (Eds.), Emotion in interaction (pp. 64–91). Oxford University Press.

Robles, J., DiDomenico, S.M., & Raclaw, J. (2021). Using objects and technologies in the immediate environment as resources for managing affect displays in troubles talk. In J.S. Robles & A. Weatherall (Eds.), How Emotions are Made in Talk (pp. 101–128). John Benjamins.

Ruusuvuori, J. (2013). Emotion, affect and conversation analysis. In J. Sidnell & T. Stivers (Eds.), Handbook of conversation analysis (pp. 330–349). John Wiley & Sons Incorporated, West Sussex.

Ruusuvuori, J., & Peräkylä, A. (2009). Facial and verbal expressions in assessing stories and topics. Research on Language and Social Interaction 42(4), 377–394.

Stevanovic, M., Henttonen, P., Koskinen E., Peräkylä A., Nieminen von-Wendt T., Sihvola E., et al. (2019) Physiological responses to affiliation during conversation: Comparing neurotypical males and males with Asperger syndrome. PLoS ONE 14(9)

Weatherall, A. (2021). Displaying emotional control by how crying and talking are managed. In J.S. Robles & A. Weatherall (Eds.), How Emotions are Made in Talk (pp. 77–97). John Benjamins.

Additional References: